The Yazidi nightmare

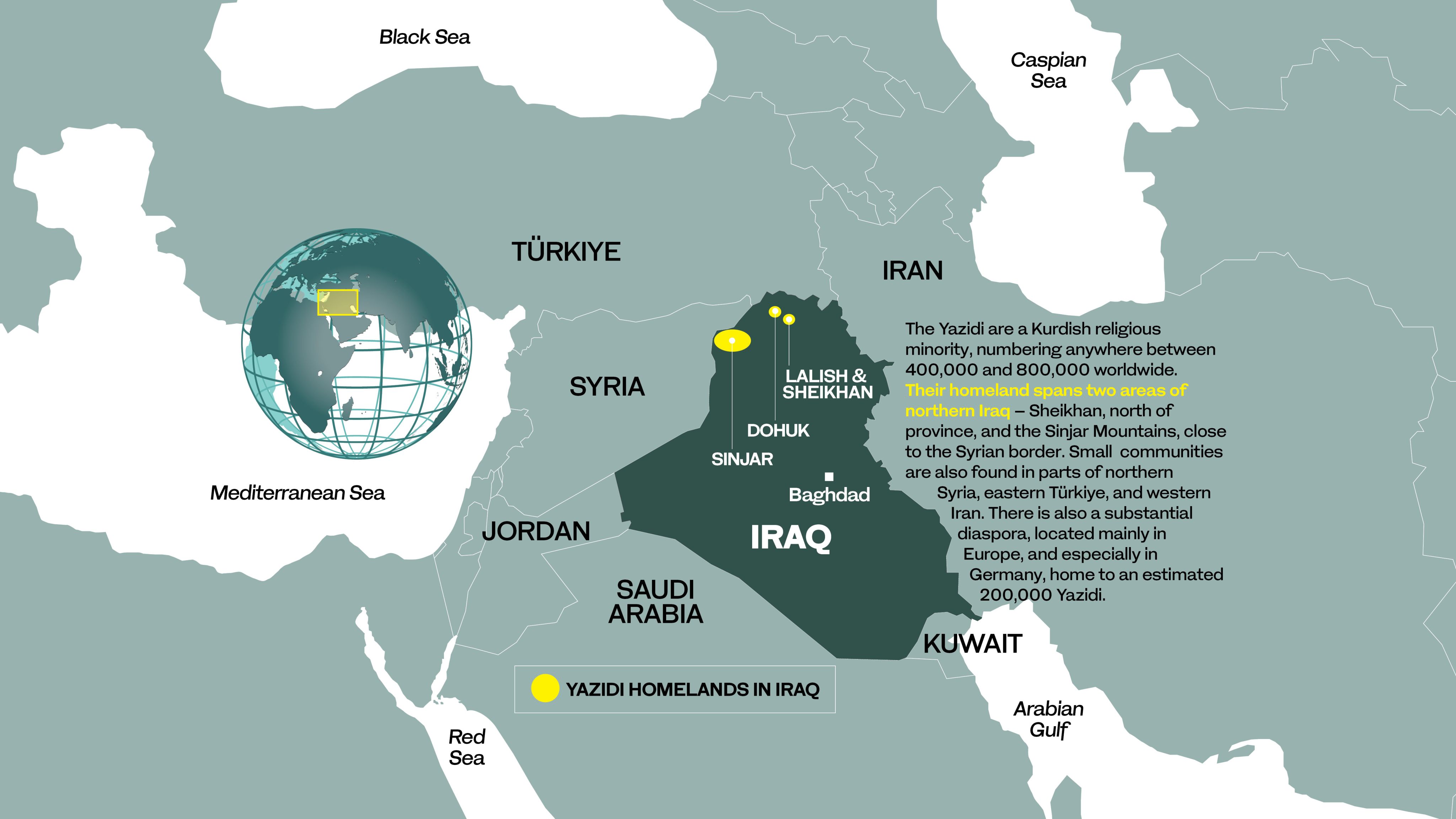

Ten years after the genocide, their torment continues

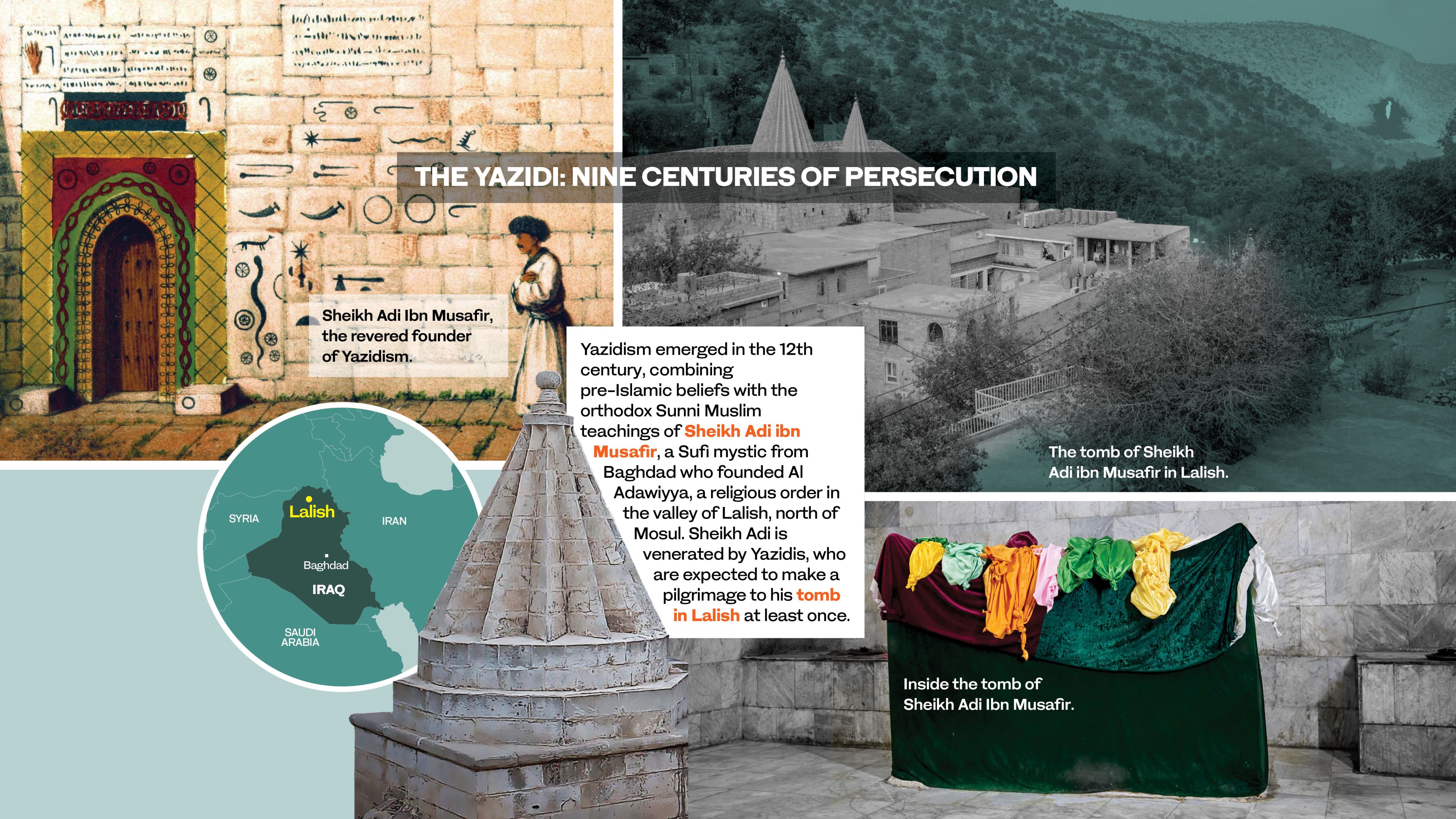

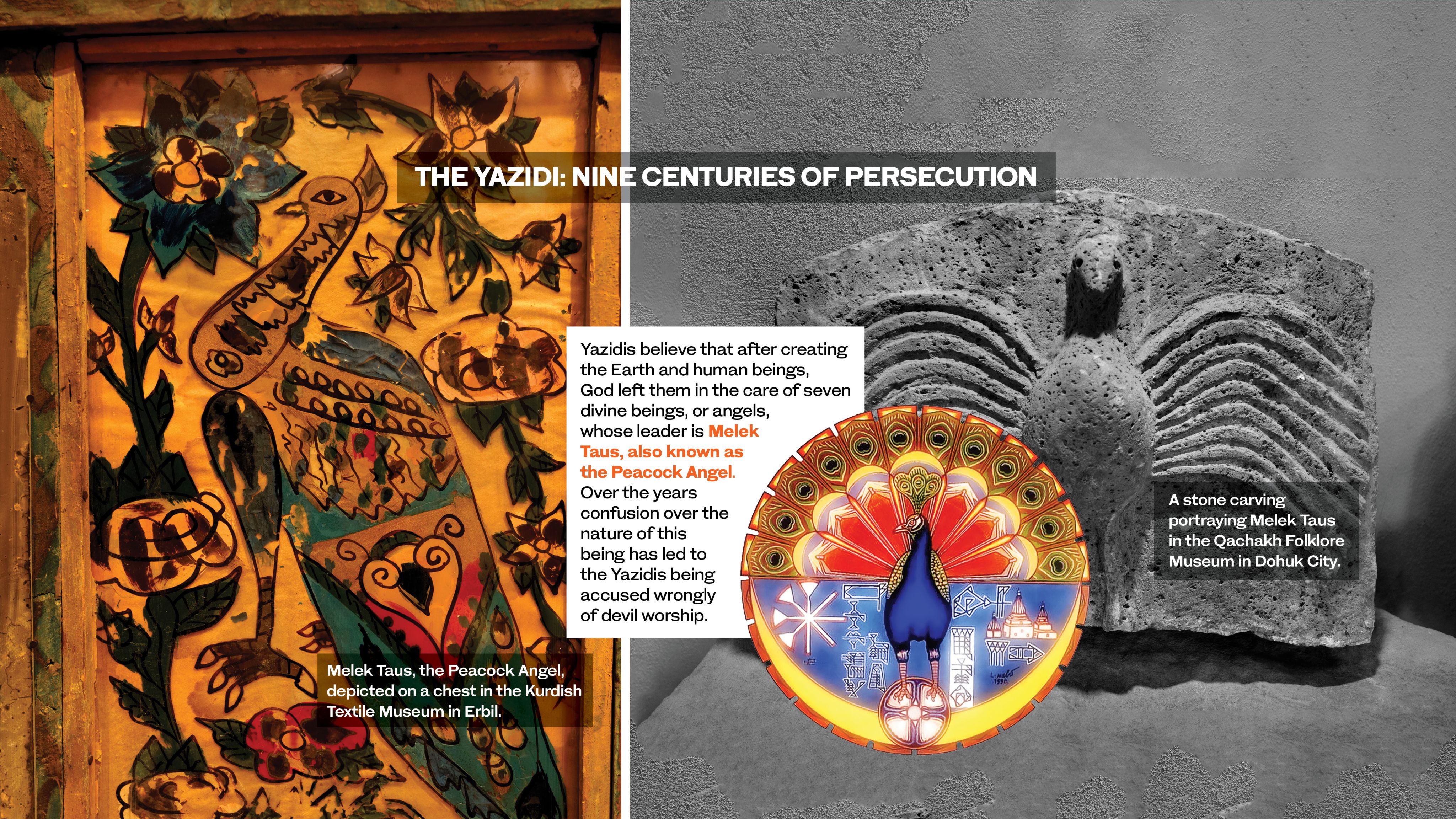

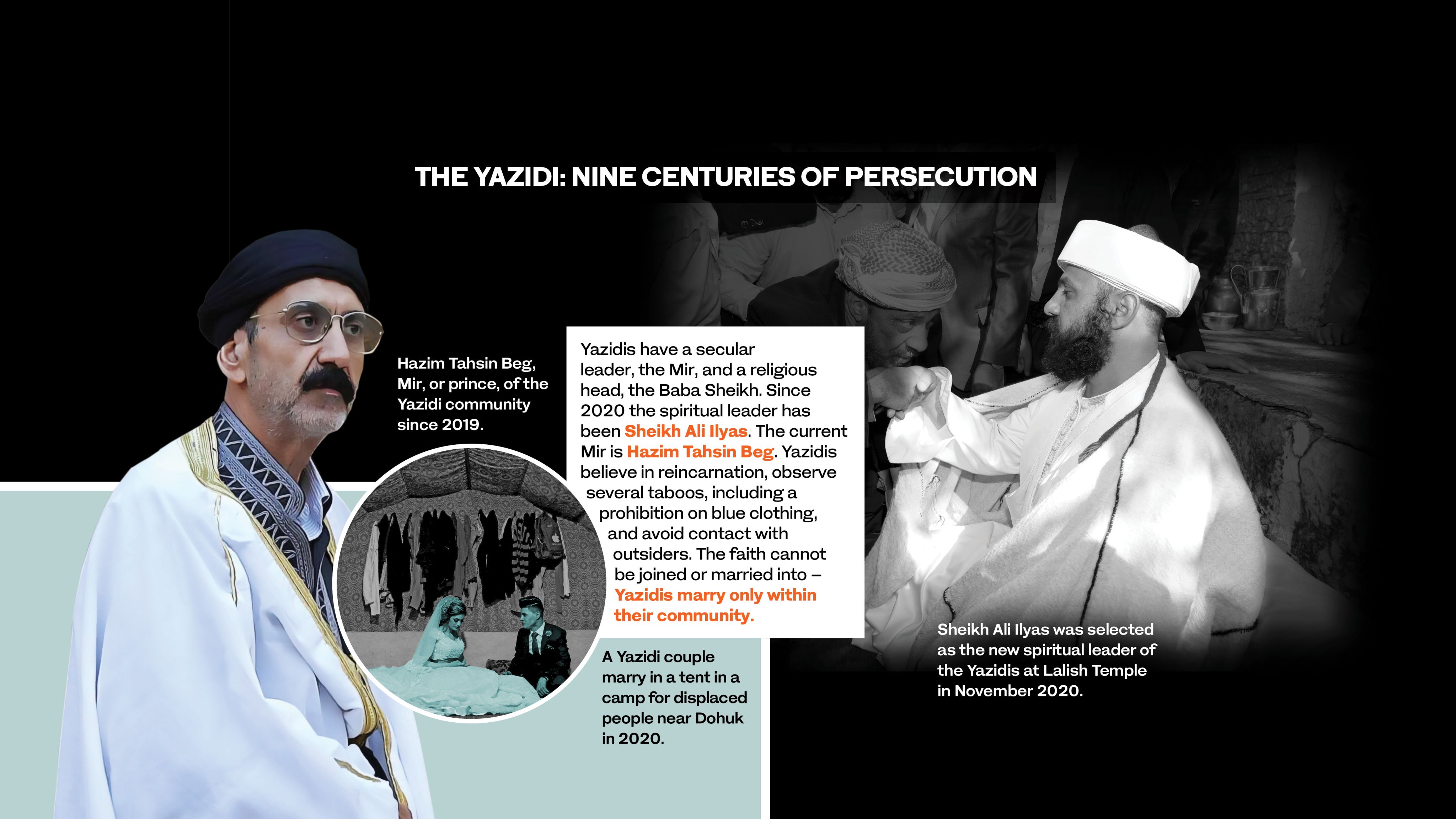

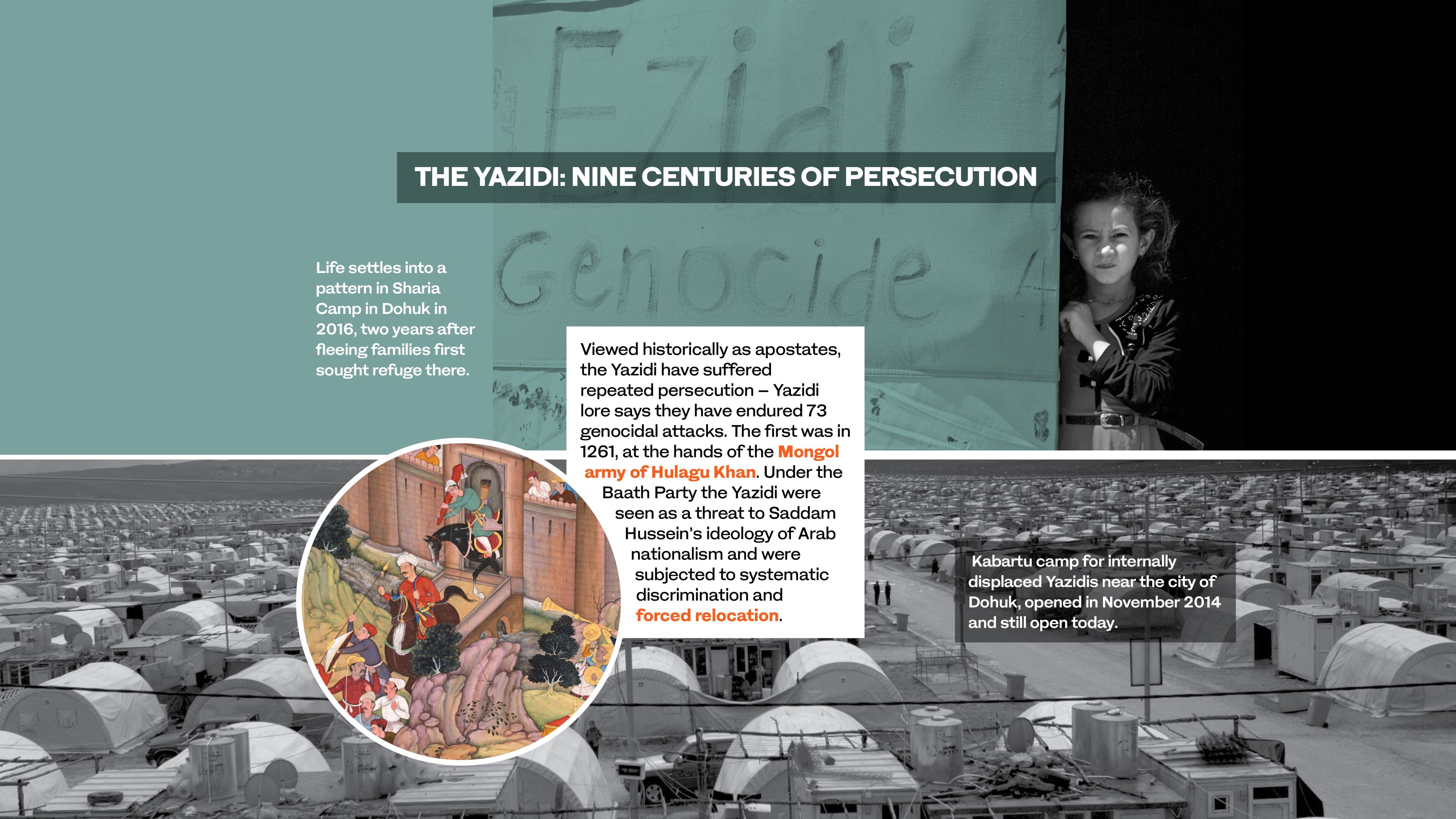

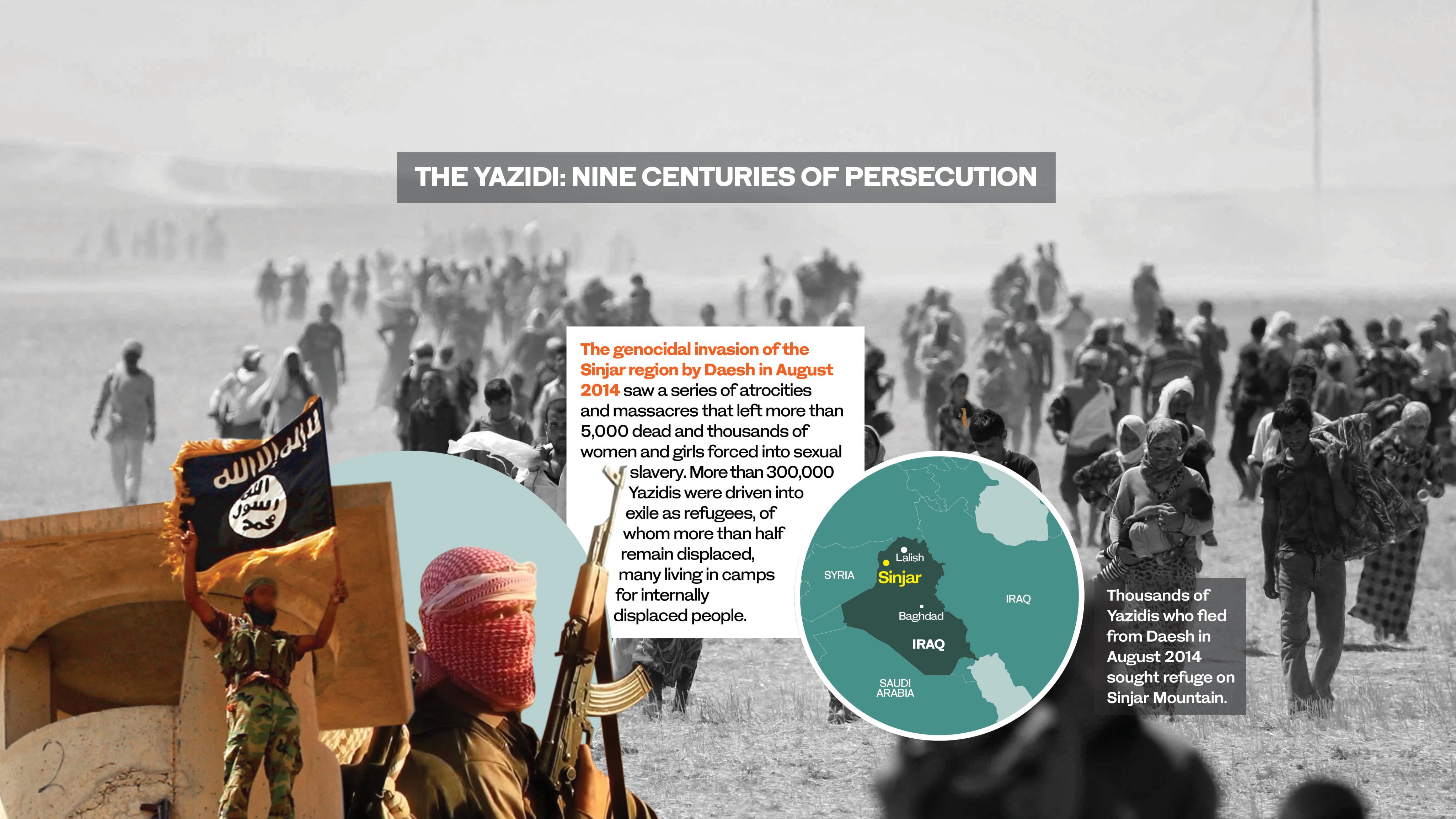

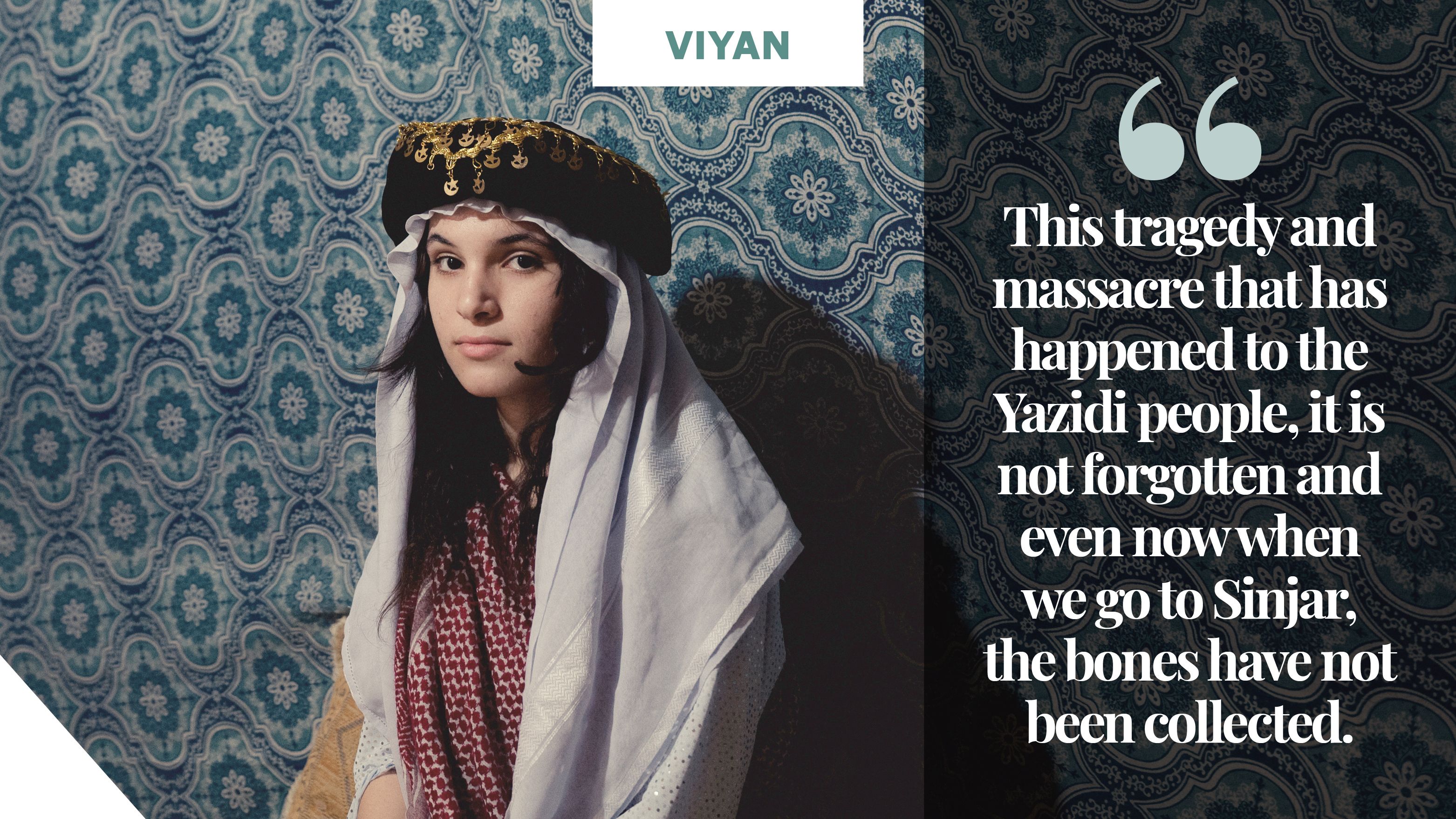

It is 10 years since the Yazidis of northern Iraq fell victim to a genocidal attack by Daesh that shocked the world. Thousands of people were murdered, their bodies thrown into mass graves. Women and children were forced into slavery and tens of thousands were driven from their homes, forced to seek refuge in tented camps for internally displaced people — refugees, in other words, in their own country.

Daesh was eventually defeated by an international coalition of forces and driven from the parts of Iraq and Syria it had occupied, which its leader, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, had proclaimed in June 2014 to be the territory of its so-called caliphate.

International attention has long since shifted to fresh tragedies, including those unfolding in Gaza and Ukraine. But a decade after the horror that was unleashed in the early hours of Aug. 3, 2014, the nightmare continues for tens of thousands of Yazidis, an ethnoreligious minority indigenous to northern Iraq and parts of Syria and Turkiye.

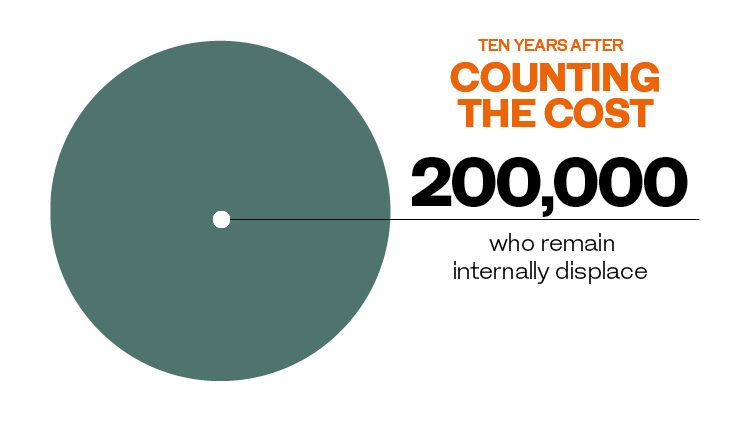

More than 200,000 of them remain in the same camps that were set up in 2014, including young children and teenagers who have known or can remember no home other than the tents in which they were born or grew up.

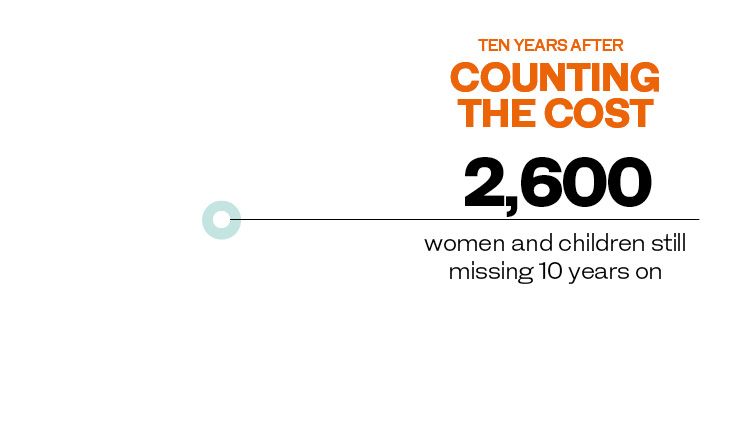

An estimated 2,600 woman and children, kidnapped into sexual enslavement and forced labor a decade ago, remain missing.

Despite the masses of testimonies from survivors and legally admissible evidence collected by the international Yazidi nongovernmental organization Yazda, not a single member of Daesh has been prosecuted in Iraq for the crime of genocide. Globally, only nine members of Daesh have appeared in court, and just one of the resultant nine convictions was for the crime of genocide committed against the Yazidi community.

According to statistics shared with Yazda by Iraq’s Mass Graves Directorate, of the 94 mass graves identified in the Sinjar district of Nineveh Governorate in northern Iraq, 33 have still not been excavated and the remains exhumed. Of the remains of 696 people recovered from the 61 mass graves that have been excavated, only 243 victims have so far been identified.

A decade on, why have the Yazidis still not been able to return to their homes and rebuild their lives?

The answer, rooted in the prejudice and persecution Yazidis have faced for centuries, lies in the weaponization of their plight by rival regional political interests that view them not as a people who have suffered for far too long but as an opportunity to be exploited.

In 2014 the Yazidis fell victim to Daesh following a series of betrayals by governments and rival forces supposedly committed to their protection. Now, denied justice, security and political representation in their own land, they remain a people betrayed, neglected and traumatized.

Darkness descends

On the evening of Saturday, Aug. 2, 2014, Haider Elias was awake late. He was making last-minute arrangements for a gathering in a public park in Houston, Texas, of a group of about 30 Yazidi families who had made the American city their home. His wife and children had already gone to bed when he received the call that made his blood run cold.

“It was from my neighbor in Houston, asking me if I had seen social media,” Elias said. “Then he said, ‘Sinjar has been invaded.’ I started calling my family and people I knew.”

After working for the US government in Iraq as a translator and cultural advisor, in 2009 Elias and his wife traveled to the US as refugees. But half a world away, his parents and siblings still lived in the family’s hometown, Tell Azeer, about 25 kilometers southwest of Sinjar city in northern Iraq.

There, it was the early hours of the morning on Sunday, Aug. 3, and the town lay directly in the path of Daesh forces advancing west from Mosul, which they had occupied since June 10.

Between midnight and 7 a.m., while his wife and children slept and as the scale of the horror unfolding more than 12,000 kilometers away became apparent, Elias made about 100 desperate calls to friends and family in Iraq.

“All I could do was encourage them to go to the mountain, run toward the mountain,” he said. “They were asking me what about this family or that family and I just said, ‘They are all in front of you.’ I kept lying to everyone just so they didn’t hesitate to go and find a safe haven from being killed or kidnapped.”

Three weeks after Daesh attacked the Yazidis, a young girl finds a temporary home in a camp for displaced people at Zakho, a few kilometers from Iraq’s northern border with Turkiye. (Getty/Pacific Press)

Three weeks after Daesh attacked the Yazidis, a young girl finds a temporary home in a camp for displaced people at Zakho, a few kilometers from Iraq’s northern border with Turkiye. (Getty/Pacific Press)

In the background of many of the calls, Elias said, “I could hear screams and shooting. There were people out of breath, who couldn’t walk or run, and sick people who were telling us they had left their medication behind.

“People were being killed … it was a nightmare. I was praying constantly that this is not real life. I will remember for the rest of my life what they went through.”

Like many in the Yazidi diaspora scattered across the US, Europe and Australia, Elias would suffer heartbreaking personal loss in the hours and days that followed.

Two of his sisters and a cousin fled with a group of about 100 neighbors and sought sanctuary in Wadiyan, a village close to Sinjar Mountain. Daesh fighters caught up with them there and began rounding up the women but were suddenly called away. Many of those who were fleeing, including Elias’ relatives, managed to make good their escape.

His father, however, had refused to leave his home, determined to defend it with an old AK-47 rifle he owned.

“I told him, ‘If Daesh see you with this weapon, they’re going to kill you right away,’” said Elias.

By some miracle, his father and about 40 other men were captured but not killed. But his younger brother, 24-year-old Falah, was not so lucky.

“I call him, he picks up the phone and nobody answers,” Elias said. “But I hear screaming and shooting. And a few hours later I hear from my other brother that he was killed.”

Falah was murdered along with two cousins. Elias’ family in Iraq was displaced to the Kurdistan Region in the aftermath of the attack, where both of his parents would die while awaiting the day they might be able to return home. One of his brothers is now in The Netherlands, seeking asylum. Another successfully migrated to Australia with his family. One of his sisters is a student at Columbia University in New York, but another sister and two brothers remain in Kurdistan, where they rent an old house.

Aug. 4, 2014: the roads to Erbil and Dohuk are jammed with vehicles as thousands of Yazidis try to escape the killing taking place in Sinjar. (Getty/Anadolu)

Aug. 4, 2014: the roads to Erbil and Dohuk are jammed with vehicles as thousands of Yazidis try to escape the killing taking place in Sinjar. (Getty/Anadolu)

In many respects, said Abid Shamdeen, who was born and raised in Sinjar and emigrated to the US in 2010, “the attack came as no surprise. There had been a gradual process: Daesh taking over parts of Syria then Mosul in Iraq and cities around Sinjar. Sinjar was one of the last parts of the whole region that Daesh took over.”

The group had taken control of Mosul almost two months previously, on June 10, and six days later advanced west and seized Tal Afar, barely 50 kilometers to the east of Sinjar.

“The Iraqi forces knew that Daesh was advancing, the Kurdish forces knew Daesh was advancing, and they put no plan in place to evacuate civilians,” said Shamdeen.

“And what happened to the Yazidi community did not happen only on Aug. 3. There had been a process of systematic violence based on identity, based on religion, in that region, especially in the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq, when terrorist attacks against Yazidis increased significantly.”

The worst manifestation of this growing animosity occurred on Aug. 14, 2007, when the Yazidis were the target of the worst suicide bomb attacks to date. Four car bombs were detonated in the towns of Til Ezer (Qahtaniyah) and Siba Sheikh Khidir (Jazeera), killing more than 800 people, injuring many more and destroying hundreds of homes.

Part of the reason the Yazidi became increasingly vulnerable, said Shamdeen, was that they were deprived of the right to self-governance and a say in their own security. Instead, it was left “in the hands of people who were foreign to the region. Forces were brought in from the Iraqi federal government, from other parts of Iraq, and the Kurdish government brought forces from the north. They didn’t know the people and as soon as Daesh arrived, they fled.”

Matthew Barber, an American academic who first visited the region in 2010 to carry out research into the Yazidis, was in Dohuk, less than three hours from Sinjar city, when the Daesh attack began.

“I had no sense that something of this scale would be coming down the road,” he said. “But I was well aware that Yazidis were highly persecuted.

“There were prevalent attitudes within society here that not only treated Yazidis as third-class citizens in a way that resembled what we would think of as racism, motivated by religious thinking, but they were also really marginalized and experienced their own existence as being under threat.”

"Help Yazidi women and children." The day after Daesh attacked, desperate Yazidis appeal for help outside the offices of the United Nations in Erbil. (AFP/Safin Hamid)

"Help Yazidi women and children." The day after Daesh attacked, desperate Yazidis appeal for help outside the offices of the United Nations in Erbil. (AFP/Safin Hamid)

As for the events that began on Aug. 3, 2014, “I place a lot of responsibility for the genocide at the feet of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (the ruling party in the Kurdistan Regional Government),” said Barber, who has remained in Iraq to continue his studies of the Yazidi people.

“Daesh was clearly the most significant actor, they conducted the genocide, but the Kurdistan Democratic Party allowed it to happen, deliberately.”

The Peshmerga, Kurdistan’s standing army, “abandoned the Yazidis as Daesh attacked. They conducted a full withdrawal without firing a single shot, without warning the civilians.

“Civilians had been asking them, ‘Should we evacuate?’ Not only did they tell them, ‘No, don’t evacuate, we will protect you,’ but they actually prevented them from evacuating. And then they withdrew and basically deliberately allowed the people to be slaughtered.”

As it did for many in the Yazidi diaspora, the day of the attack passed in a blur of anxious phone calls and mounting horror for Shamdeen, who was studying in the US at the University of Nebraska at the time and living in the city of Lincoln.

“It was a feeling of helplessness,” he said. “You are witnessing, in real time, a genocide unfolding in your homeland, targeting your friends, family and people you grew up with, but you can’t do anything about it. All you can do is scream and say, ‘Something needs to be done.’”

The events of that day are etched into his memory in vivid detail.

“Everything was happening in haste, families were fleeing,” he said. “I remember being on a short Skype call with my little brother, Shaalan. They were on the north side of the mountain and I asked him to please, just leave and flee as soon as you can; do nothing, do not look back, just keep going north as much as you can. That’s your only chance.”

Shaalan, who was just 15 years old, took his brother’s advice. He and other members of the family fled to the camps for internally displaced people in the Kurdish region, and from there to camps in Turkiye. Eventually he made his way to Europe, where he is now lives and attends college in Belgium.

“They were lucky enough, because they were on the north side, to make it to the Kurdish region before Daesh reached our town,” said Shamdeen. “But so many others didn’t make it because, within hours, Daesh captured many Yazidi villages.”

Very soon after the attack began, thanks in part to the anxious advocacy of Yazidis in the US, including Shamdeen and Elias, the entire world was alerted to the atrocities being perpetrated against the Yazidis by Daesh. Within days, US President Barack Obama authorized airdrops of food and water, and targeted airstrikes to protect tens of thousands of Yazidis and others under siege on Sinjar Mountain.

In shock, but safe for now: two days after fleeing Sinjar, the women and children of one Yazidi family find sanctuary in a school in the Kurdish city of Dohuk. (Getty/Safin Hamid)

In shock, but safe for now: two days after fleeing Sinjar, the women and children of one Yazidi family find sanctuary in a school in the Kurdish city of Dohuk. (Getty/Safin Hamid)

“Today,” Obama said during a televised address on Aug. 7, 2014, “America is coming to help.”

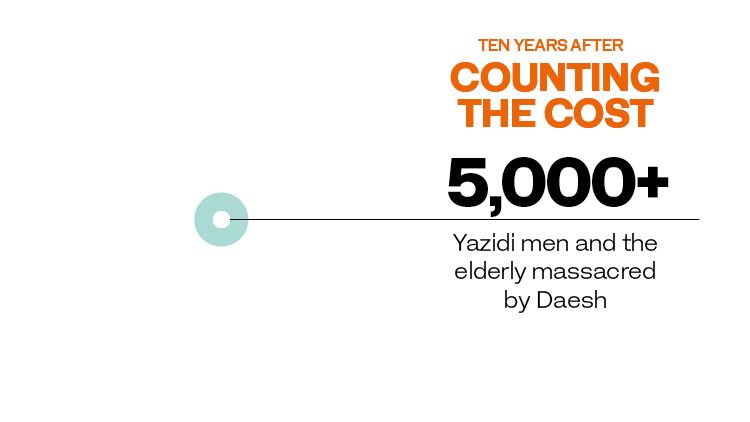

In the event, efforts to save the Yazidis from the madness of the persecution by Daesh would prove to be much more complex than simply ordering numerous airstrikes. In fact, it would be 2017 before Sinjar was finally liberated. By then, about 400,000 Yazidi had been displaced, more than 5,000 men and older women killed, and at least 6,000 women and children kidnapped and sold into slavery.

In Sinjar, Daesh left behind a landscape scarred by mass graves, with schools, hospitals, homes, farms and electrical and water infrastructure destroyed, and a population deeply traumatized by the unimaginable horrors they had endured.

The experiences of many were summed up by an account given to the Yazidi nongovernmental organization Nadia’s Initiative by “Samar,” who was 10 years old when she kidnapped and taken with other children to a kindergarten.

“There, they taught us the Qur’an,” she said. “Once, they gave us poison. We thought we died. We spent two weeks in the hospital.”

Then their captors devised an obscenely macabre lottery.

“There were three things, which were marriage, death and serving a Daesh family,” said Samar. “Each kid got a different paper. Based on that, some were killed, some were given to their fighters as wives, others were chosen to be servants in their houses. I was chosen to be a servant. I served a house for two years.”

Many of the horrific details of the Daesh occupation of Sinjar emerged in “The Last Girl,” the harrowing 2017 memoir by Nadia Murad, who as a 21-year-old was taken as a sex slave when her village of Kocho was occupied on Aug. 15.

“The devastating thing is that the village was surrounded for about two weeks, from Aug. 3 until Aug. 15,” said Shamdeen. “We knew that Daesh had killed the men that they captured on Aug. 3, and that in other villages they had taken women and children into captivity.

“We were communicating with US officials, with Iraqi officials and Kurdish officials, trying to communicate the message that Daesh will commit a massacre in Kocho. But they didn’t get any help.”

On Aug. 7, 2014, US President Barack Obama authorised airstrikes to protect American personnel in Erbil, and airdrops of supplies to Yazidis trapped on Sinjar Mountain. (Alamy)

On Aug. 7, 2014, US President Barack Obama authorised airstrikes to protect American personnel in Erbil, and airdrops of supplies to Yazidis trapped on Sinjar Mountain. (Alamy)

Daesh herded hundreds of villagers into the local school, where the men were separated from the women. The latter were taken upstairs to a room where their money, jewelry, cellphones and ID cards were taken from them.

From the windows they watched as the men, and boys deemed to be adolescents after a cursory inspection to see if they had hair under their arms, were loaded onto trucks and driven away to be murdered. In all, 600 people died, including six of Murad’s brothers and half-brothers. The women in the school could hear the gunshots that killed their sons, brothers and husbands.

Dozens of older women who were considered too old to be sold as sex slaves were also killed, including Murad’s mother, Shami.

The fate that awaited Murad and many other young women from Kocho, including underage girls, was sexual slavery. They were driven to Mosul and sold to Daesh fighters and supporters. An estimated 3,000 Yazidi women were enslaved.

Murad’s ordeal continued until November 2014, when she managed to escape her captor. She found her way to a camp for displaced people and from there applied successfully to become a refugee in Germany, arriving there in 2014.

That might have been the end of Murad’s story but instead she chose to become a tireless advocate for her people. She met world leaders and highlighted the Yazidi cause in global forums, including the UN Security Council in New York, which she addressed in December 2015.

In 2016, she was appointed the UN’s first goodwill ambassador for the dignity of survivors of human trafficking.

In 2018, she and Shamdeen co-founded Nadia’s Initiative, a non-profit organization committed to the redevelopment of Sinjar, with a mission “to create a world where women are able to live peacefully, and communities that have experienced trauma and suffering are supported and redeveloped.” They also became engaged.

That same year, Murad became the first Iraqi and first Yazidi to win the Nobel Peace Prize, in recognition of her “efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict.”

As the nightmare in Kocho and the other villages in Sinjar continued to unfold, members of the scattered Yazidi diaspora rallied to bring their plight to the attention of the world.

In the US, Elias and a group of fellow Yazidis from Houston set off for Washington, first to raise awareness of the crisis and then to liaise with the US State Department. Elias co-founded Yazda, an organization dedicated to support the Yazidi and other communities persecuted because of their identities or beliefs, and to pursue justice for the victims of the genocide perpetrated by Daesh.

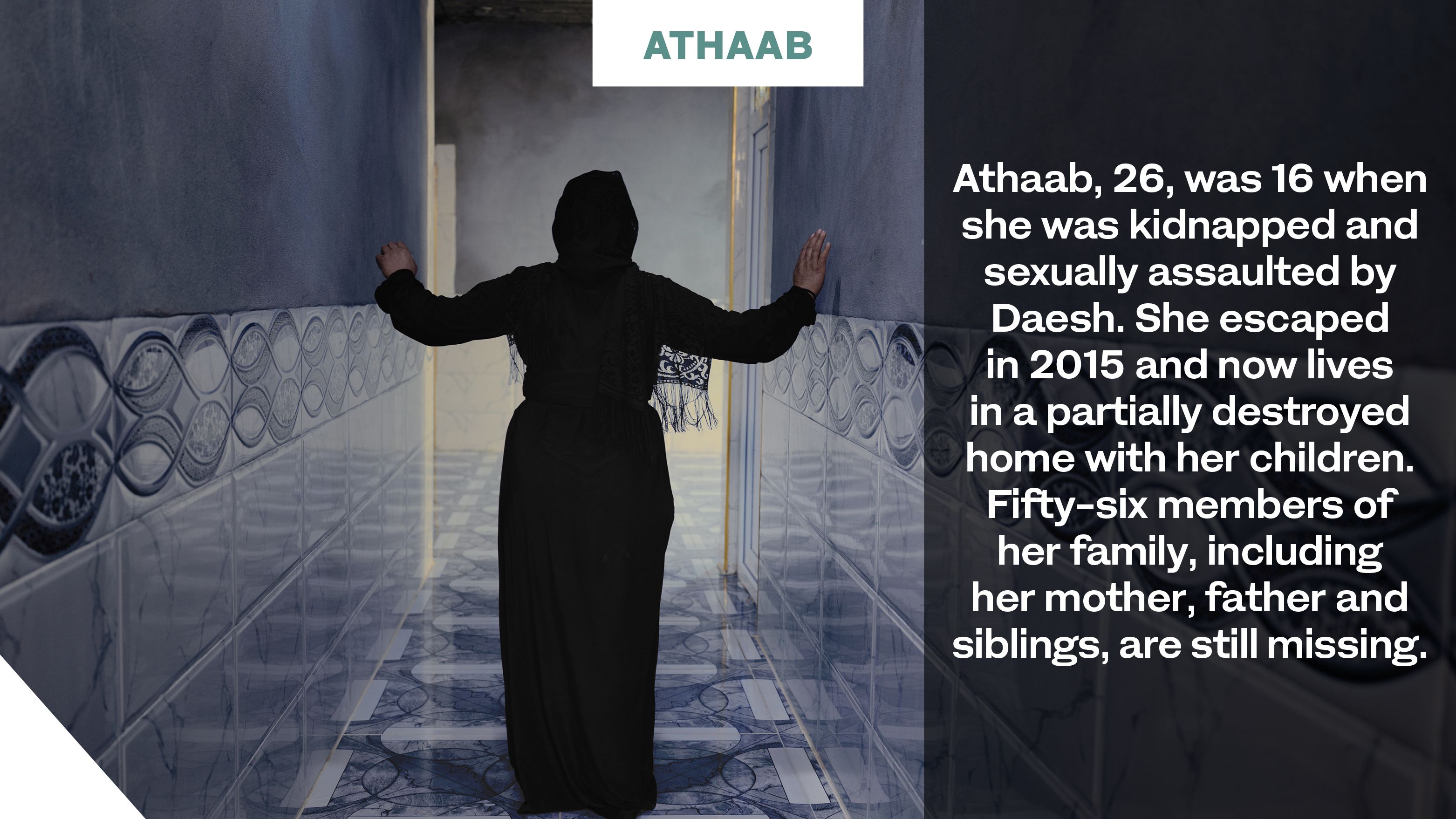

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Athaab receives psychosocial support through local partners of Save the Children.

Going home

Reparation for the Yazidis has been hard to come by. Since 2005, Iraq’s central government has provided a compensation scheme for citizens affected by terrorism called the Martyr Foundation. However, Yazidis have struggled to access the funds to which they are entitled as compensation for property that was stolen from them and homes that were destroyed.

Although northern parts of the Kurdistan region were liberated fairly quickly after the attacks in 2014, the south remained under Daesh control for three years “and during that time nearly 80 percent of the homes were destroyed,” said Elias. Those that survived, now abandoned for a decade, have been thoroughly looted.

“For three years, people came and took appliances and anything that was beneficial to them, such as door frames and windows and anything metal, water storage tanks, everything except the walls,” said Elias.

He has personal experience of the devastation. When he visited Iraq a couple of years ago and visited his former home in the town of Tell Azeer, about 25 kilometers southwest of Sinjar city, “all that was left were the window holes and the door holes. Everything else was gone.” Books and family photo albums had been burned.

A decade on from the genocide, much of the city of Sinjar, devastated in fighting in 2014 and 2015 between Daesh and Kurdish forces, remains in ruins.

A decade on from the genocide, much of the city of Sinjar, devastated in fighting in 2014 and 2015 between Daesh and Kurdish forces, remains in ruins.

The Martyr Foundation, he said, “has money, it has the budget, and unfortunately a lot of people, especially in the south in Baghdad and those who know somebody, are overly compensated.

“But compensation for the Yazidi has been extremely slow. We know that about 28,000 families have registered for compensation, and that fewer than 1,000 have been compensated.”

In cases where Yazidi claims for lost property have been met, “the value of the compensation is cut by 50 percent. So if you have a home that’s destroyed and is worth $10,000, you will automatically receive only $5,000,” Elias said.

“They claim it’s a budgetary issue but it’s just a decision they make and we feel the Yazidi are being discriminated against.”

Yazidis who return home face another problem, rooted in the era of Saddam Hussein, because they were denied property rights, including the official registration of properties that they owned; discrimination that Elias said has directly affected his family and their home.

Although 160,000 Yazidis have returned to Sinjar, many of the damaged and long-abandoned homes in the region have been looted and are uninhabitable.

Although 160,000 Yazidis have returned to Sinjar, many of the damaged and long-abandoned homes in the region have been looted and are uninhabitable.

“That has now created a huge issue for Yazidis whose homes have been destroyed because even though the Iraqi government recognizes the Ba’ath crime of stripping the rights of the Yazidis, they still technically couldn’t compensate my father or myself, because I didn’t have the title of the home. And that’s the case for all the Yazidis,” he added.

“If you can’t be compensated for the real estate, you aren’t able to reconstruct your home.”

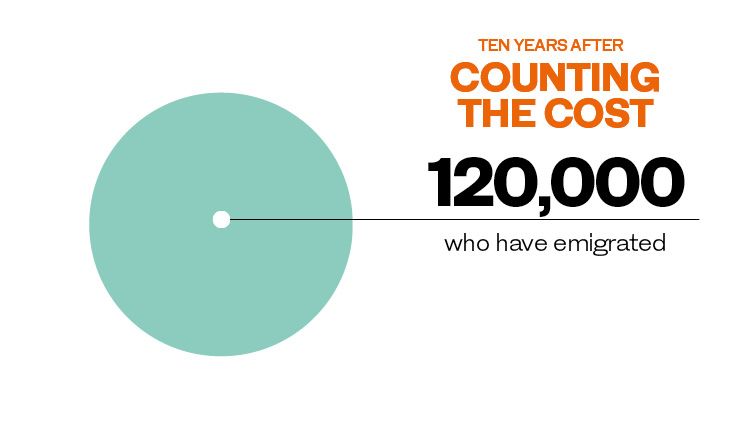

Although about 160,000 Yazidis have returned to their homeland, if not their original homes, a similar number have emigrated and 200,000 remain in camps for internally displaced people or are otherwise living elsewhere in the country.

Returning to Sinjar is not a decision to be taken lightly. The situation there is complex and insecure because the region has become the plaything of rival political groups, its people treated as pawns to be exploited.

“The camps for internally displaced people were meant to be a temporary solution for people to be able at some point to return to their areas,” said Natia Navrouzov, the executive director of Yazda.

“But over the past 10 years the security situation in Sinjar has worsened and one of the reasons people don’t return is because of the instability of the area, which leads to insecurity, lack of services, infrastructure and functioning institutions, and access to employment.

“Currently in Sinjar you have many different players with different interests and the interests of civilians and their daily needs are being neglected.

“You have the Iraqi army, you have the Peshmerga, supported by Kurdistan. On top of that you have the PKK (the Kurdistan Workers’ Party), which came in and is now occupying the mountains, and they’re bombed by Turkiye quite regularly because Turkiye wants to get rid of them.”

The economic situation, which is linked to the insecurity, “is also very bad. People cannot find employment and sometimes the only option they might have is to be militarized and join one of these forces, which of course we don’t want.

“The international community should be aware that if you send people back to an area without any access to services or employment, then they will become desperate, and desperation leads to extremism.”

To make matters worse, the future of the few dozen camps for displaced people is now at the mercy of a political dispute between the Iraqi central government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government in Erbil.

For the past decade Kabartu camp, near Dohuk, has been home to many of the 200,000 Yazidis who today are still refugees in their own homeland.

For the past decade Kabartu camp, near Dohuk, has been home to many of the 200,000 Yazidis who today are still refugees in their own homeland.

“The federal government wants to close the camps because Baghdad wants to portray itself as a stable country that does not need any humanitarian help, that doesn’t need any international interference or UN support, and that is linked to the broader Iranian agenda,” said Navrouzov.

“Then on the other hand you have Kurdistan, where these camps are located, which is saying conditions are not yet right for Yazidis to return to Sinjar, so the camps must remain open. The Yazidis are stuck in between and not really knowing what’s going to happen.”

The proposed closure of the camps was first mooted three years ago. Most recently, the Iraqi government said the camps must close by the end of July, three days before the 10th anniversary of the genocide that led to their creation. This order is heading for the courts as the Ministry of Displacement and Migration in Baghdad has filed a lawsuit against the Kurdistan Regional Government.

For now, the camps remain open. But in essence, said Navrouzov, “the minister is saying if they don’t close the camps, aid will stop.

“The message from us is that we want people to be properly supported when they return. Instead of receiving only 4 million IQD (US$3,400) families returning should receive more and at least enough to rebuild their houses.

“We also want stability for people who return and functioning institutions in Sinjar so that they do not end up having to go to different cities for administrative procedures. We also ask Baghdad to ensure that there is electricity, water, schools and hospitals in the areas to which people return.”

Many Yazidis have decided to leave Iraq in the hope of finding a better life elsewhere.

There are thousands of children who were born or grew up in the camps over the past 10 years, and who know no other way of life.

There are thousands of children who were born or grew up in the camps over the past 10 years, and who know no other way of life.

“There is no Yazidi family that doesn’t have members who have fled Iraq,” said Navrouzov. "A lot of them have family in Germany, France, the US or Australia, and often what they want is just to join them because they think there’s no future for them in Iraq.”

In theory, said Elias, the return of the Yazidis to Sinjar “shouldn’t be complicated. They were displaced. Daesh was militarily defeated. Now they should get compensation to rebuild their homes, reconstruct the education and public-service infrastructure, and they should come back.”

However, the political and economic interests at play ensure that the situation remains extremely complicated indeed.

In early July this year, the Iraqi prime minister’s office established a committee of representatives from the central and Kurdish regional governments to develop “a joint humanitarian plan to resolve the issue of internally displaced persons, in collaboration with specialized UN agencies.”

At the time of writing, however, no further details about the committee or its work have been made public.

Arab News sought comment on the issues raised in this report from both the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government. Neither responded.

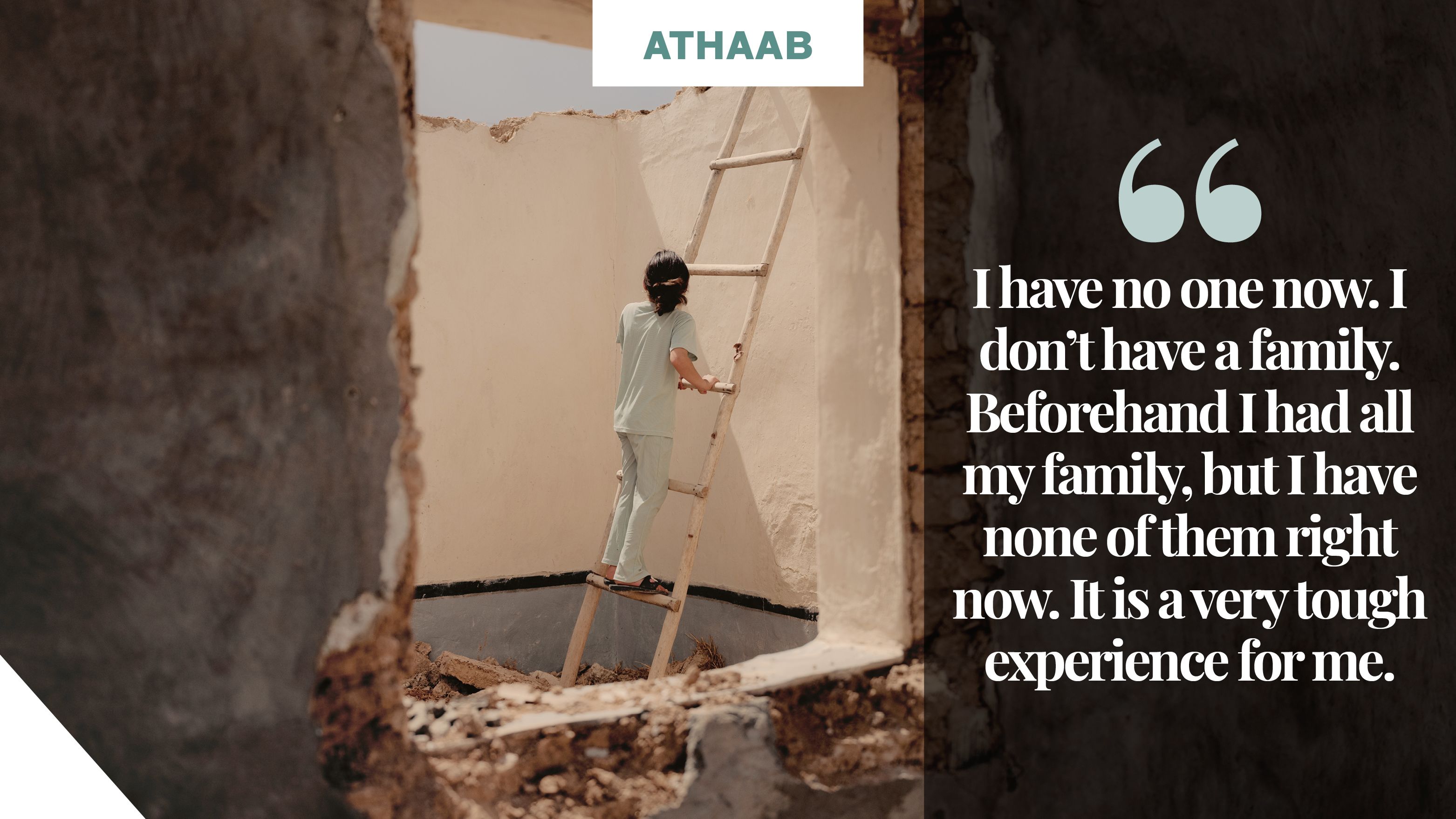

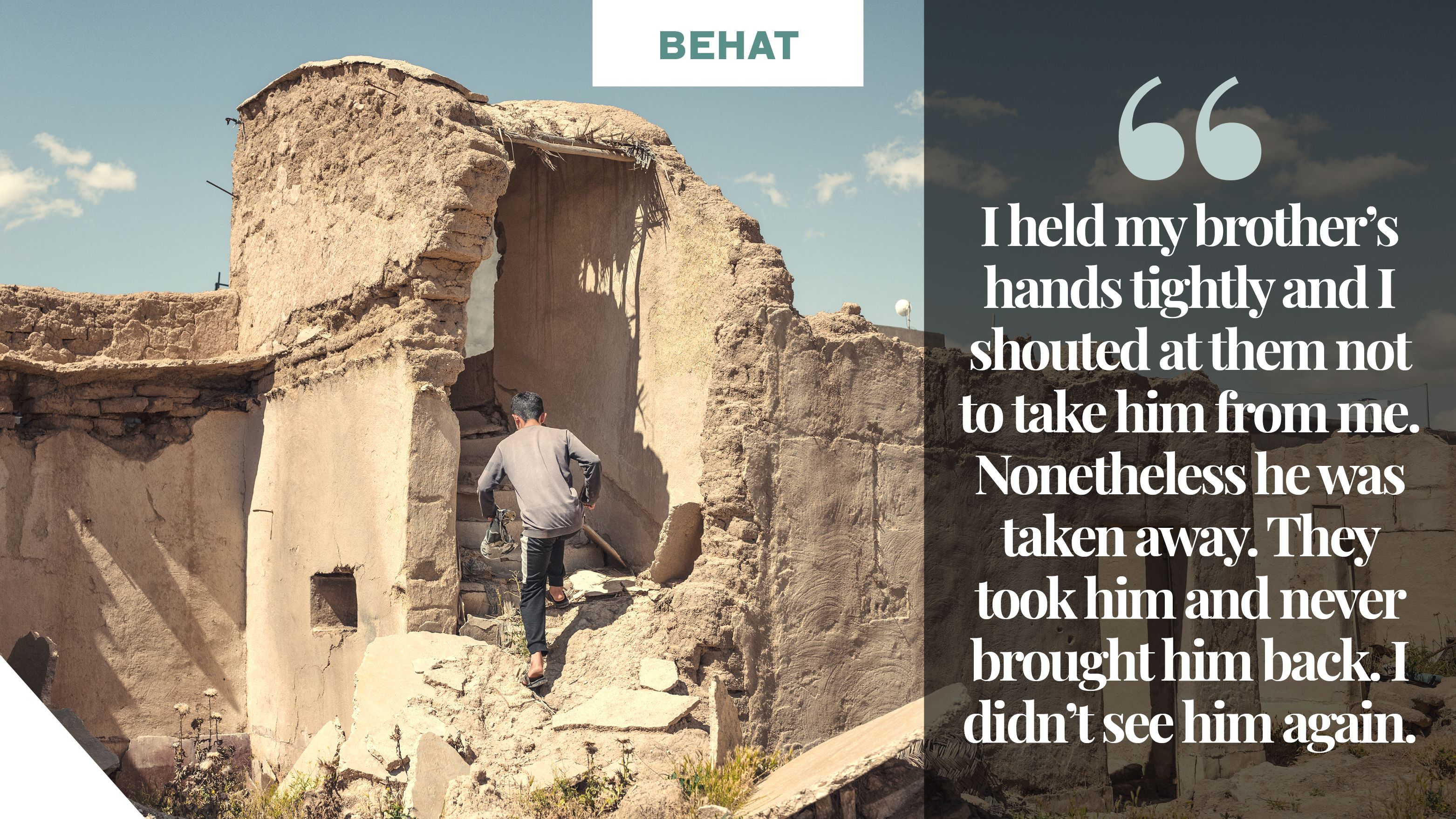

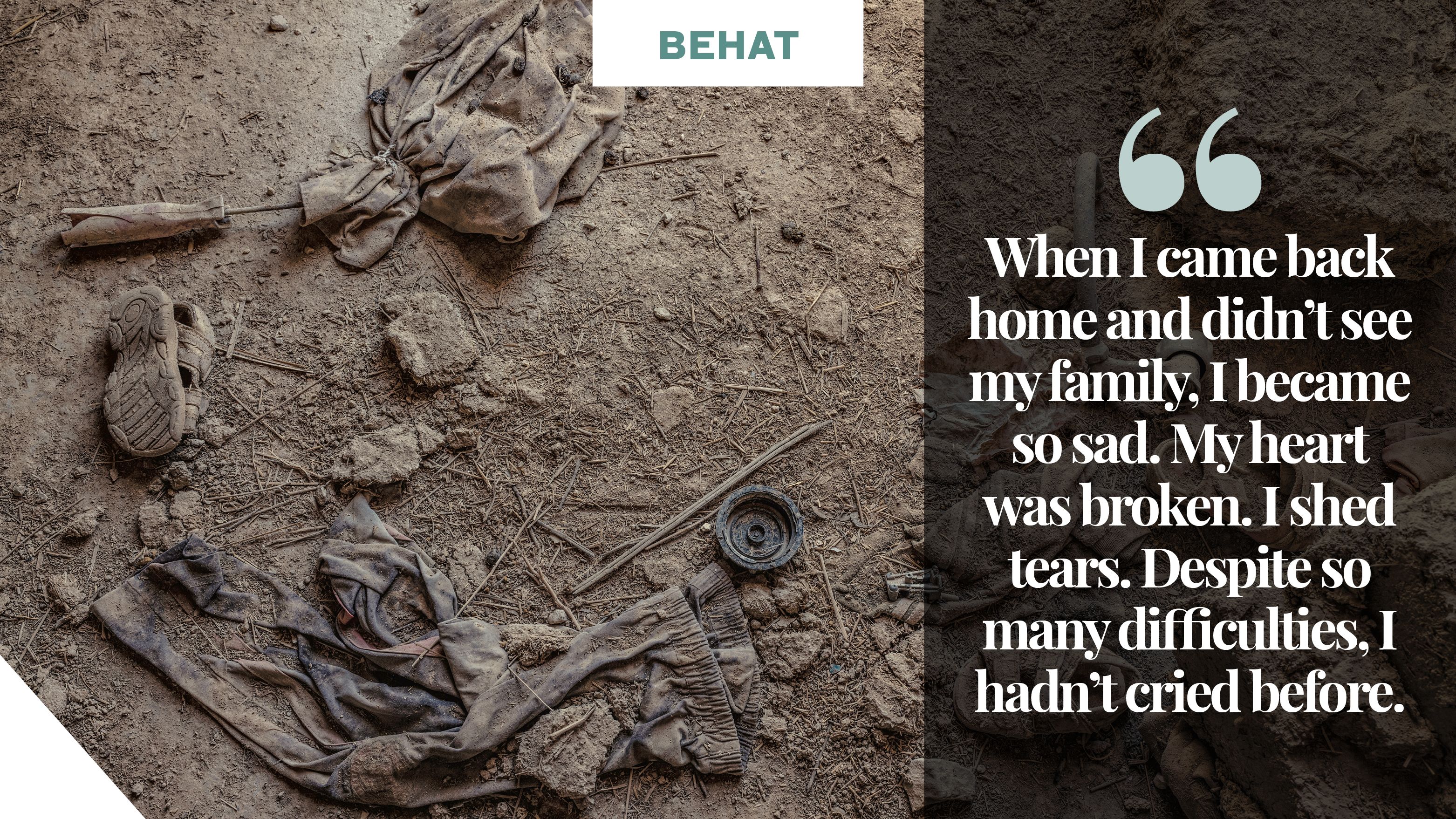

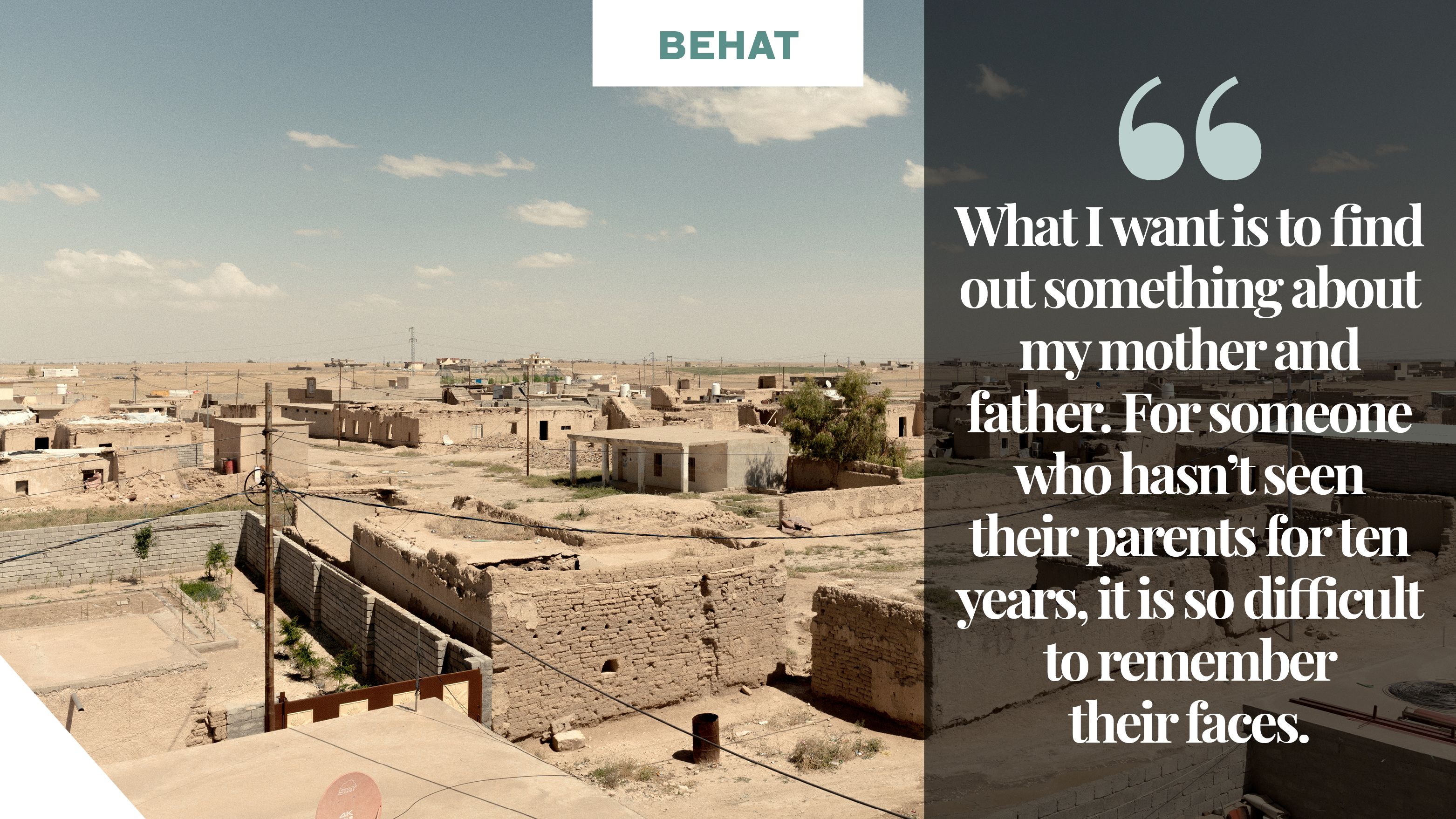

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Behat receives child protection services through Save the Children’s partners.

Recovering the dead

It is not only the threat of the imminent closure of the camps that is causing distress among Yazidis. In September 2017, responding to a request from the Iraqi government for help in bringing members of Daesh to justice, the UN Security Council set up an investigative team to collect, preserve and store evidence of acts committed in Iraq that might amount to war crimes, crimes against humanity or crimes of genocide.

For the past six years, the UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Daesh/ISIL in Iraq (UNITAD for short) has worked alongside Iraqi authorities, including the Mass Graves Directorate, which is part of the Martyrs Foundation, and the Ministry of Health’s Medico-Legal Directorate.

UNITAD has provided expertise, training and equipment to help with a range of activities, including digital surveys of mass grave sites, crime scene reconstructions, evidence collection, the development of facilities for the storage of biological materials, victim identification, and the return of remains to families for burial.

But with the task of exhuming and identifying the remains of victims far from complete, UNITAD’s mandate is due to expire on Sept. 17. Many fear that with the imminent end of the team’s mission, the evidence of Daesh crimes it has painstakingly gathered will never be used to hold those responsible to account, and that the Yazidis therefore will be forever denied the justice they seek in Iraq.

UNITAD’s work began in Kocho, Nadia Murad’s home village and the site of more than a dozen mass graves, in March 2019.

Of the 5,000 or more Yazidis murdered by Daesh in Sinjar, Iraq’s Mass Graves Directorate, backed by UN experts, has so far recovered 696 victims, of whom only 243 have been identified. (Safin Hamid)

Of the 5,000 or more Yazidis murdered by Daesh in Sinjar, Iraq’s Mass Graves Directorate, backed by UN experts, has so far recovered 696 victims, of whom only 243 have been identified. (Safin Hamid)

Murad’s mother was among more than 80 Yazidi women buried in one such grave, located close to Solagh Village in Sinjar. Now known as the Grave of the Mothers, it is the site of the Yazidi Genocide Memorial. Paid for by the US Agency for International Development and with funds from Murad’s Nobel Peace Prize award, it was built by Nadia’s Initiative in partnership with the International Organization for Migration in Iraq.

During a speech at the inauguration of the memorial in October 2023, Murad said it stands “as a reminder of the depths humanity can sink to, but it also stands as a testament to the strength and resilience of the surviving Yazidi community as they rebuild their lives after genocide.”

It is her hope that the memorial will provide “closure and healing for those families who were not reunited with the bodies of their loved ones,” and as such represents “one step on the road to justice.”

But, she added, the community cannot continue along the path to healing without more help from Iraqi authorities.

“Building this memorial should not have been left to the local community, in the same way that the rebuilding of Sinjar should not be the sole responsibility of Yazidis and the international community,” Murad said.

“We need more resources from the Iraqi government and we need regional stability so displaced Yazidis can return home.”

UNITAD was introduced as a mechanism intended to help achieve justice for all of the communities that suffered under Daesh. But its work has focused the most on the dead of the Yazidi community and, advocates for the community say, that work remains distressingly incomplete.

UNITAD is now working on the last mass grave it will help to exhume before its mandate expires. Located in Tal Afar, it is thought to be the largest such burial site in Iraq and to contain the remains not only of victims of Daesh, but also others, from the eras of Saddam Hussein and Al-Qaeda.

A spokesperson for UNITAD told Arab News there are “strong indications that this site contains victims from the Yazidi and Shiite communities,” and that “so far, the team has supported national counterparts in the Mass Graves Directorate, assisted by the Medico-Legal Directorate, in excavating 156 bodies from Bir Alou Antar mass grave, and work continues in this site.”

Almost five years on from the massacre, relatives of the missing gather in the village of Kocho in March 2019 to witness the opening of the first Yazidi mass grave. (AFP/Zaid Al-Obeidi)

Almost five years on from the massacre, relatives of the missing gather in the village of Kocho in March 2019 to witness the opening of the first Yazidi mass grave. (AFP/Zaid Al-Obeidi)

According to statistics obtained by Yazda from the Iraqi Mass Graves Directorate, no fewer than 94 mass graves and 49 individual graves have been identified in Sinjar. So far, the remains of 696 people, including women, children and men, have been recovered.

But, said Navrouzov, “out of 696 Yazidi victims recovered, only 243 have been identified so far and 33 mass graves have not yet been excavated.”

Now, she added, “with the closure of UNITAD, it is unclear who will support the Iraq Technical Team, the Mass Graves Directorate and the Medico-Legal Team to continue this long and complex process.”

For five years until her appointment as Yazda’s executive director, Navrouzov headed up the NGO’s legal advocacy efforts and documentation project, gathering evidence of Daesh crimes and coordinating with UNITAD and foreign states that were willing to prosecute nationals accused of such crimes.

A Yazidi from Georgia, Navrouzov was still studying when Daesh attacked her community in Iraq. She moved to Iraq and joined Yazda in 2018.

“As a woman, a lawyer and a member of the Yazidi community, I always felt that the only way to help my people was to move to Iraq,” she said.

“Because of my legal background, I became very active in that field and continue to be so.”

She was in Kocho when excavation work began at the first mass grave.

“It was the moment that I really realized we were working on a genocide,” she said. “You hear about the crimes and you see survivors, but when you are standing in front of a mass grave and they’re just bringing the remains out, one by one, it is just very, very shocking.

“We mainly document survivors’ testimonies but also crime scenes, and we had documented these mass graves in Sinjar years before,” she said. “So when the exhumation started, of course we were very relieved because for once there was some movement on that front.

“But it was a very terrible, distressing moment for the families, and we were there mainly to support them.”

Mourners gather around graves in Kocho village where the remains of 104 Yazidi victims recovered from mass graves are reburied in February 2021. (AFP/Zaid Al-Obeidi)

Mourners gather around graves in Kocho village where the remains of 104 Yazidi victims recovered from mass graves are reburied in February 2021. (AFP/Zaid Al-Obeidi)

Part of that support included arranging for psychologists to be on hand, and liaising between the relatives, who had many questions, and UNITAD.

Navrouzov said that when she arrived in Kocho, “one thing that really struck me was that it was now an empty village. No one was there, apart from some Yazidi fighters who had decided to stay to protect these mass graves until they were all exhumed. They feared that one day Daesh might come back and try to destroy the evidence.

“That was very powerful for me. Some of these men had been part of groups that were taken and executed, but they survived because they ended up under a pile of bodies.”

Remains exhumed from the mass graves in Sinjar are taken to Baghdad to begin the frustratingly lengthy process of identifying them.

“Identification is still going on and that’s another problem,” Navrouzov said. “Often people think that you just exhume and the process is done, but in a way the hardest part is the identification.”

In Baghdad, the Mass Graves Directorate collects DNA samples from relatives to compare with samples taken from the remains.

“But because a lot of Yazidis have left Iraq, or don’t trust the authorities, and also because the authorities don’t have enough staff and resources and technology, all of these factors make it a very slow process,” said Navrouzov.

“We have people contacting us and saying, ‘This mass grave was opened years ago; where are the bones? When will I be able to bury my family members?’

“This issue affects people’s daily lives and their mental health. A lot of people who have had opportunities to leave Iraq and resettle have stayed or returned because they cannot leave their missing behind, either in mass graves or, perhaps, alive somewhere in captivity.”

The international community, Navrouzov added, “has to realize that when we say we need exhumations and the return of the people who are missing, it’s not just something that needs to happen for justice. Do we want Yazidis in two or three generations from now to be still carrying that trauma?”

The Yazidi genocide memorial in Solagh village outside Sinjar, inaugurated on Oct. 18, 2023, by former Daesh captive and Nobel Peace Prize winner Nadia Murad. Her mother was murdered nearby. (Nadia’s Initiative)

The Yazidi genocide memorial in Solagh village outside Sinjar, inaugurated on Oct. 18, 2023, by former Daesh captive and Nobel Peace Prize winner Nadia Murad. Her mother was murdered nearby. (Nadia’s Initiative)

There is deep concern about what will happen to the process when UNITAD concludes its work in Iraq in September.

“UNITAD has helped the Iraqi national team a lot and both have built good relations with each other and with NGOs such as Yazda,” said Navrouzov. “Our work was complementary.

“But the Mass Graves Directorate and the Medico-Legal Department have only small teams and do not have enough resources to continue this process alone. Iraq is full of mass graves, not just from the Daesh crimes but also from the previous regimes. All need to be exhumed.

“When I speak to authorities in Iraq, they tell me they don’t want resentment to be created because the international community focuses on Yazidis, and there are of course mass graves from other communities that haven’t been exhumed for decades.

“I have felt that resentment and that’s why I think there has to be global, holistical support to Iraq, not just for Daesh, because everything is linked. All these cycles of violence are intertwined.”

The end of UNITAD’s work, Navrouzov said, “will not mean the end of the exhumations process, because the Iraqi team leading this will still be around. But it will mean that it will have less technical and forensic support, and it also means that it will be slower — and it’s already slow.

“We need to make sure that when UNITAD closes, its forensic team, in some form or another, continues to work in Iraq. For the sake of the victims, survivors and their families, this work must continue.”

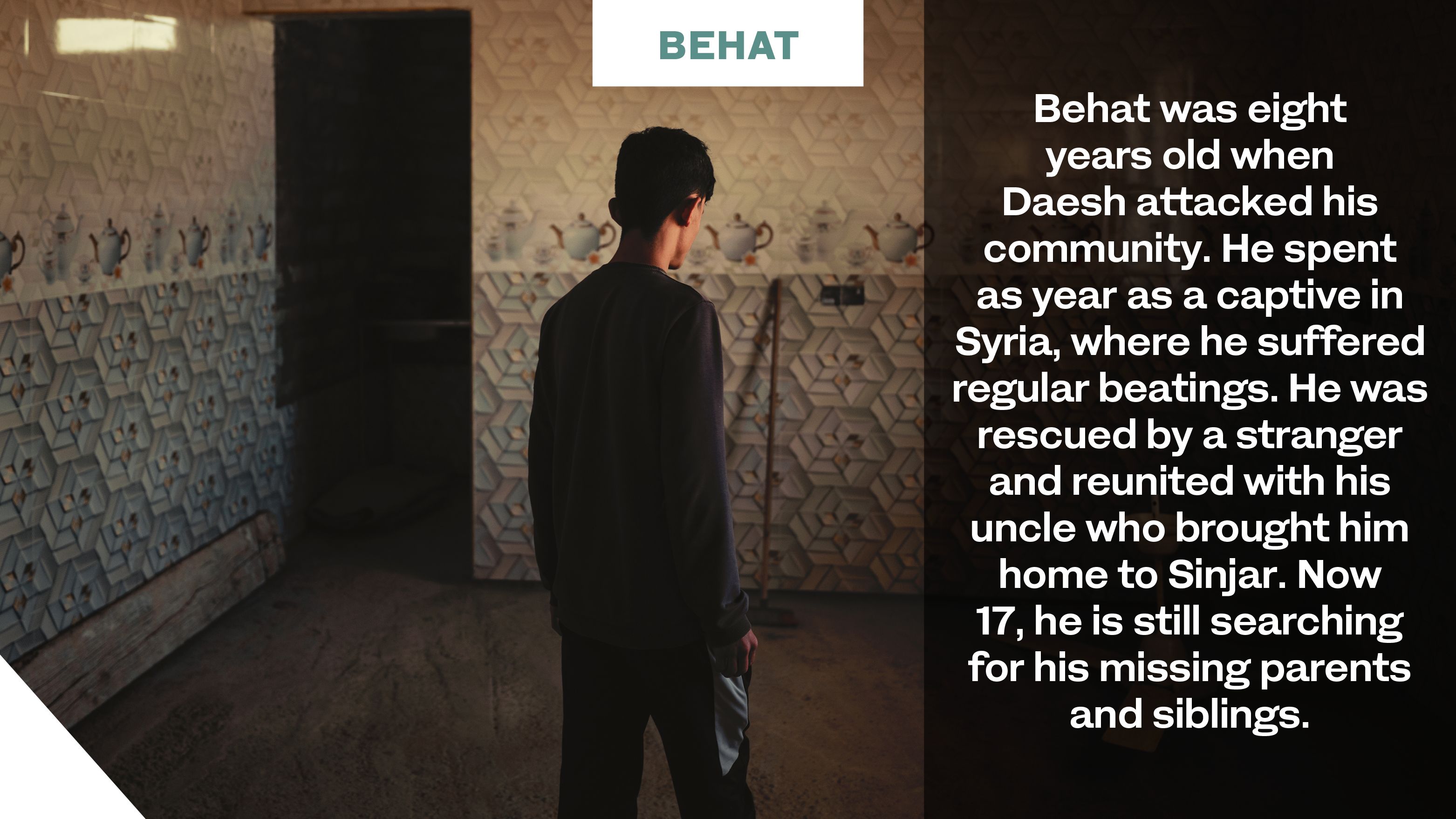

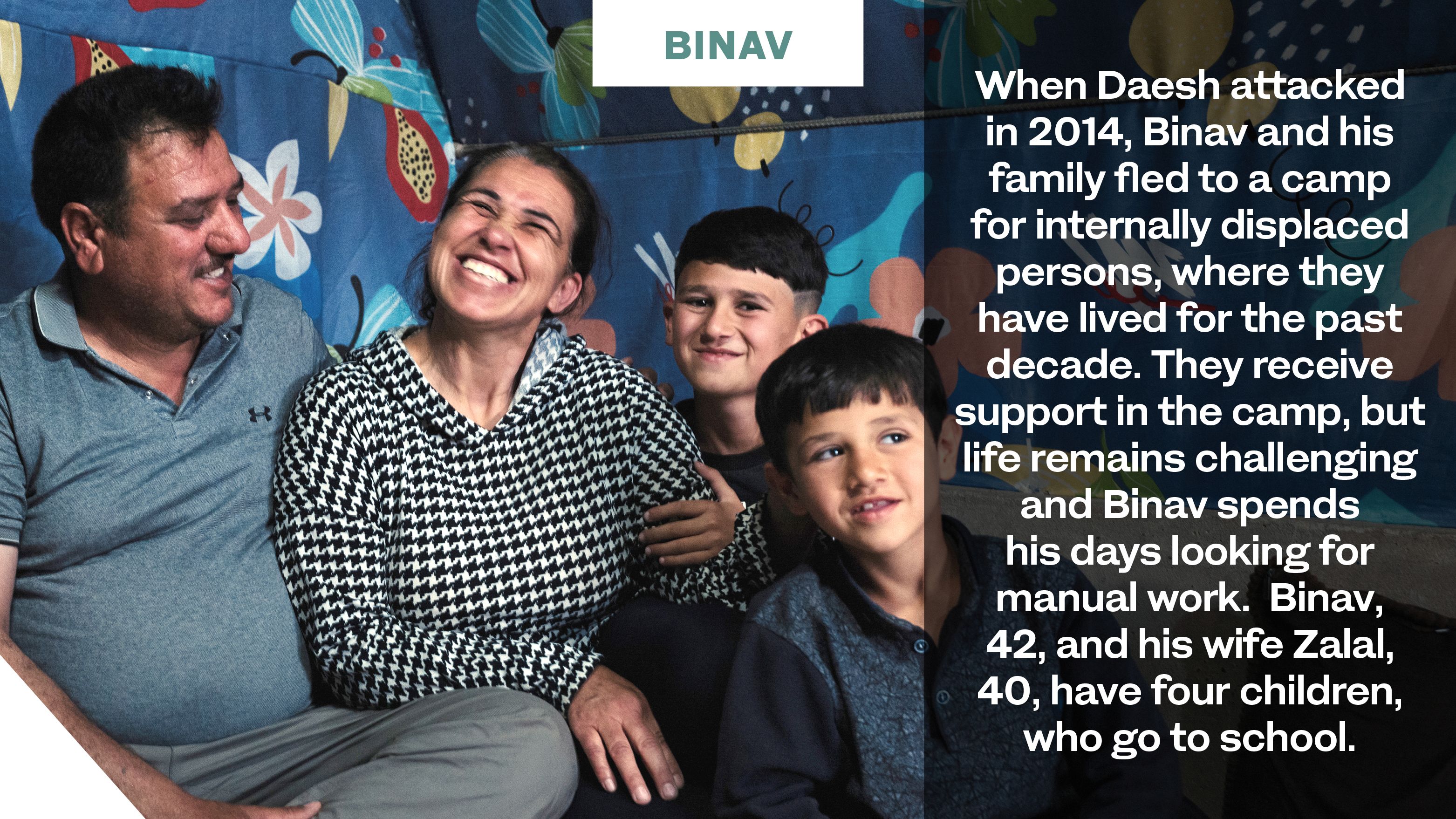

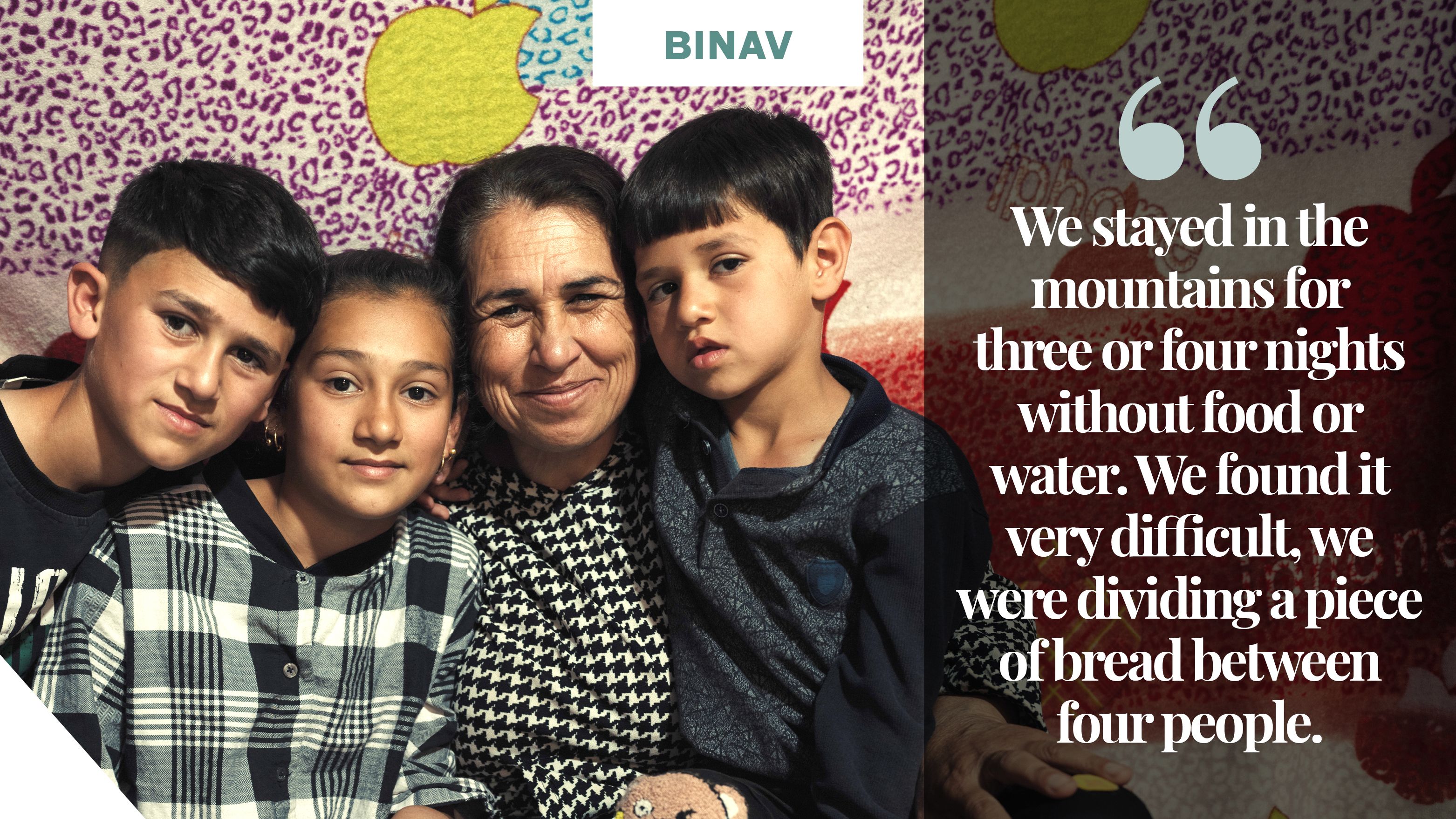

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

Binav’s family receives child protection support through Save the Children.

The quest for justice

There is concern among the Yazidi community, at home and abroad, that the end of UNITAD will also mean the disruption of the already inadequate process of bringing the criminals of Daesh to justice, in Iraq and around the world.

Many members of Daesh were foreign fighters from North America, Europe, Asia and parts of the Middle East.

“The UN team has collected so much evidence that could be used to put Daesh on trial,” said Shamdeen.

“But that unit’s mandate is ending, as we commemorate the 10th anniversary of the genocide, and it seems the international community, the UN member states, the UN Security Council, all have no plan as to how to move forward.”

It is, he said, “still unclear how the evidence will be preserved, how it will be used and where it will be used.”

In an address to French senators, the French Yazidi community and international human rights leaders on June 24 this year at the Palace of Luxembourg in Paris, Navrouzov said: “We thought we had time. We still have many witnesses who are ready to speak who want to give their testimonies to UNITAD.”

In July 2021 a former member of Daesh known as Omaima A was found guilty by a court in Germany of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity for her involvement in the enslavement of two Yazidi women. (Chris Emil Janssen)

In July 2021 a former member of Daesh known as Omaima A was found guilty by a court in Germany of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity for her involvement in the enslavement of two Yazidi women. (Chris Emil Janssen)

Ten years later, Iraqi authorities have not put a single member of Daesh on trial for the crimes of genocide and sexual violence against Yazidis. Instead, former members of Daesh are tried under a terrorism law “because anybody they can convict of terrorism, they can execute,” said Murad Ismael, a co-founder and former president of Yazda. No longer associated with the NGO, he has since founded Sinjar Academy, an educational nonprofit organization that supports the socioeconomic recovery of the community through the provision of quality education.

Ismael, who now lives in Lincoln, Nebraska, was a graduate student in Houston when Daesh attacked his homeland in 2014. As they were for many Yazidis in the global diaspora, those were dark days for him. He left Iraq in 2009, two years after siblings emigrated. Their mother followed them in 2012. His father was deceased but when Daesh attacked in 2014, Ismael still had many aunts and uncles living in Iraq.

Many of them escaped to the mountains but one aunt was captured, with her family, in Sinjar city. Another, his mother’s sister, had a son with special needs who was killed by Daesh on the first day of the genocide.

Proof of membership of Daesh is evidence enough for the Iraqi judiciary to convict a suspect but this means that no details of the atrocities carried out against Yazidis are ever revealed in court. Survivors do not have the opportunity to give their testimonies and victims and their families are denied the degree of closure that acknowledgment of, and accountability for, their suffering might bring.

“We never hear that this person went to this village and killed this many and enslaved this many, or was in charge of this camp where captives were held,” said Ismael. “There are no details.

“This is justice in darkness, which is not justice at all. They may have executed many Daesh members but we don’t recognize it as justice. I want to see these people talking about what they’ve done, why they did it, who funded them, who instructed them to do it — how this whole thing happened.”

Trying suspects solely on charges of terrorism, said Navrouzov, “is just a way to get rid of the problem without really addressing the root causes, without addressing the full extent of the crimes.”

She added: “There are reports of how, sometimes, Daesh members admit to the judge that they had enslaved Yazidis but then this part of the narrative is completely disregarded because the mentality is, ‘OK, this person ultimately will be executed.’

"Jennifer W" traveled from Germany to Syria with her Iraqi husband, Taha Al Jumailly, in 2014. She imprisoned and took part in the murder of a Yazidi child, killed in front of her enslaved mother, and in August 2023 was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

"Jennifer W" traveled from Germany to Syria with her Iraqi husband, Taha Al Jumailly, in 2014. She imprisoned and took part in the murder of a Yazidi child, killed in front of her enslaved mother, and in August 2023 was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

“Going for terrorism is easier, so why bother going to the threshold that you need to reach to demonstrate genocide?”

There was one such example on July 10, when an Iraqi court sentenced a widow of the former Daesh leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi to death by hanging under Iraq's anti-terrorism law.

This approach has left many victims fearing they will never achieve justice or closure.

“Some Yazidis have even tried to participate in these terrorism trials, because their perpetrators were so clearly identified,” said Navrouzov.

“But there was pressure from the tribe of the suspect. It’s a very tribal community, so even if you have someone in your tribe who was a Daesh member, you will try to defend the honor of your tribe.

“So they would either pay off the potential Yazidi witnesses, or threaten them, and people would back off. That’s why we needed the international community, entities such as UNITAD and witness protection units, and why we needed a specialized tribunal to be set up with Iraq to just clean up this whole process and make it a rule-of-law process, not based on tribal interests or politics or anything like that. But it never happened.

“And of course, right now Yazidis don’t feel justice and many of them just don’t see any future in Iraq because of that.”

But Navrouzov refuses to give up hope that justice will eventually be done.

“Iraq has promised several times now to pass legislation to enable prosecution for core international crimes. We hope the law will be passed soon and will include consultations of survivors and NGOs working directly with them. We have also heard from UNITAD that the Iraqi judiciary is interested in these types of prosecutions, and we are willing to support them as long as requirements around witness protection, due process and the well-being of survivors are upheld.”

She added: “Having worked in this field for six years now, sometimes I do feel like it’s endless, but I do want to believe trials will happen at some point. After all, there are still trials now of people who committed crimes in Rwanda, and even under the Nazi regime.”

Activists and legal teams fighting for the rights of those affected by the genocide carried out by Daesh believe the survivors deserve the opportunity to share their stories, and to see those responsible for the horrors they endured brought to justice before it is too late.

“We owe it to the survivors because a lot of them stepped up, denounced these crimes and gave their testimonies,” said Navrouzov.

“We have enough evidence. I think the problem right now is the politics; how much do countries really want to prosecute Daesh? With everything else happening in the world, with Ukraine and Palestine, I think the attention right now has shifted a lot, which is really distressing to the Yazidi survivors we are trying to support.

In November 2021 Iraqi Taha Al Jumailly became the first member of Daesh to be convicted of genocide. He was jailed for life in Germany for murdering a five-year-old Yazidi girl in front of her mother. (AFP)

In November 2021 Iraqi Taha Al Jumailly became the first member of Daesh to be convicted of genocide. He was jailed for life in Germany for murdering a five-year-old Yazidi girl in front of her mother. (AFP)

“All victims deserve justice. There should be no hierarchy or race for attention.”

Overseas, the picture is slightly more encouraging. Several countries have put on trial, or are planning to try to do so, citizens who joined Daesh to hold them accountable for their part in the atrocities in Iraq.

“We have had nine successful convictions in Germany of Daesh members for crimes against Yazidis, including three for genocide,” said Navrouzov. “Ten years on, this is a good achievement, in a way. There are some other contexts where it has taken decades to have anything in place.

“But of course, when you compare that to the scale of the crimes committed by many nationalities of people who joined Daesh, then of course it’s a drop in the ocean, it’s not enough.”

Eight of the nine trials that have taken place in Germany were of women, the wives and former wives of Daesh members, rather than front-line fighters. This, said Navrouzov, is a product of political decisions made by authorities in some European countries to allow only women and children who wanted to be repatriated to come home.

She does not believe that only the fighters should be prosecuted, “because Daesh was a whole system, with complicit judges and bureaucrats who enabled the whole system.

“The women are often described by female Yazidi survivors as being worse than their husbands. They were not only often enabling the rapes but participating in them. We had female Daesh members who prepared Yazidi captives for rapes, putting makeup and clothes on them.

“I think that ultimately everyone should be prosecuted for the extent of their crimes, and female Daesh members played a big role in these crimes. But obviously the men should be prosecuted as well.”

The sole exception to the trials of women in Germany to date was the very first case, in 2021, in which a 29-year-old Iraqi man, Taha Al-Jumailly, became the first member of Daesh to be convicted of genocide against the Yazidi.

A court in Frankfurt heard that in 2015, Al-Jumailly and his German wife bought a captured Yazidi woman and her 5-year-old daughter, Reda, and kept them enslaved at their home in Fallujah, Iraq. Mother and daughter, who were regularly beaten and suffered other abuses, lived in constant fear. Reda died after she was tied to the bars of a window, outside in scorching heat, as punishment for wetting the bed.

Nadia Murad, right, at the UN with human rights lawyer Amal Clooney, who told the Security Council that "the crimes committed by ISIS against women and girls are unlike anything we have witnessed in modern times." (SOPA Images)

Nadia Murad, right, at the UN with human rights lawyer Amal Clooney, who told the Security Council that "the crimes committed by ISIS against women and girls are unlike anything we have witnessed in modern times." (SOPA Images)

Reda’s mother participated in the court proceedings as a co-plaintiff, after being tracked down and interviewed by Yazda as part of its documentation program to gather evidence against Daesh members. Al-Jumailly’s conviction, and the life sentence he received, were confirmed by the German Federal Court of Justice in 2023.

At the time, Nadia Murad, herself a survivor of enslavement and abuse at the hands of Daesh, said that such convictions were “vital to our healing process; they let us know that the world has seen and condemns the efforts to eradicate the Yazidi people.”

Al-Jumailly, she added, “was the first to be convicted of genocide but he will not be the last.”

After Al-Jumailly’s trial two more convictions for genocide followed in Germany, both of female German nationals. Jalda A., who had travelled to Syria in April 2014 and married several high-ranking Daesh fighters, was sentenced to 5 years and 6 months in prison in May 2022.

Nadine K., who joined Daesh with her husband in late 2014, after the invasion of Sinjar, was sentenced to 9 years and 3 months in June 2023. The couple had held a Yazidi woman, referred to only as N, as a sex slave. She was repeatedly raped and beaten.

N gave evidence during the trial, after which she thanked the German authorities and said: “The justice that I hope to achieve through this trial not only concerns me personally but also our Yazidi community … I allow myself to speak on behalf of all survivors, stating that as individuals and as a Yazidi community, we can only process what happened to us if we experience justice.’

After the trial, British human-rights lawyer Amal Clooney, who represented N, praised “the bravery of survivors, like my client, who were raped and enslaved by ISIS but were determined to face their abusers in the dock.

“In this trial my client stared down the ISIS member who enslaved her for three years. And today, she won. Thank you to Germany, which has led the world in bringing ISIS to justice.

“As the judge said in court today – there is a word for what ISIS did: and it is genocide. Thanks to trials like this, the world knows this. And the survivors deserve nothing less.”

Other countries are now set to follow Germany’s lead, with trials scheduled to take place this year and next in The Netherlands, Sweden and France.

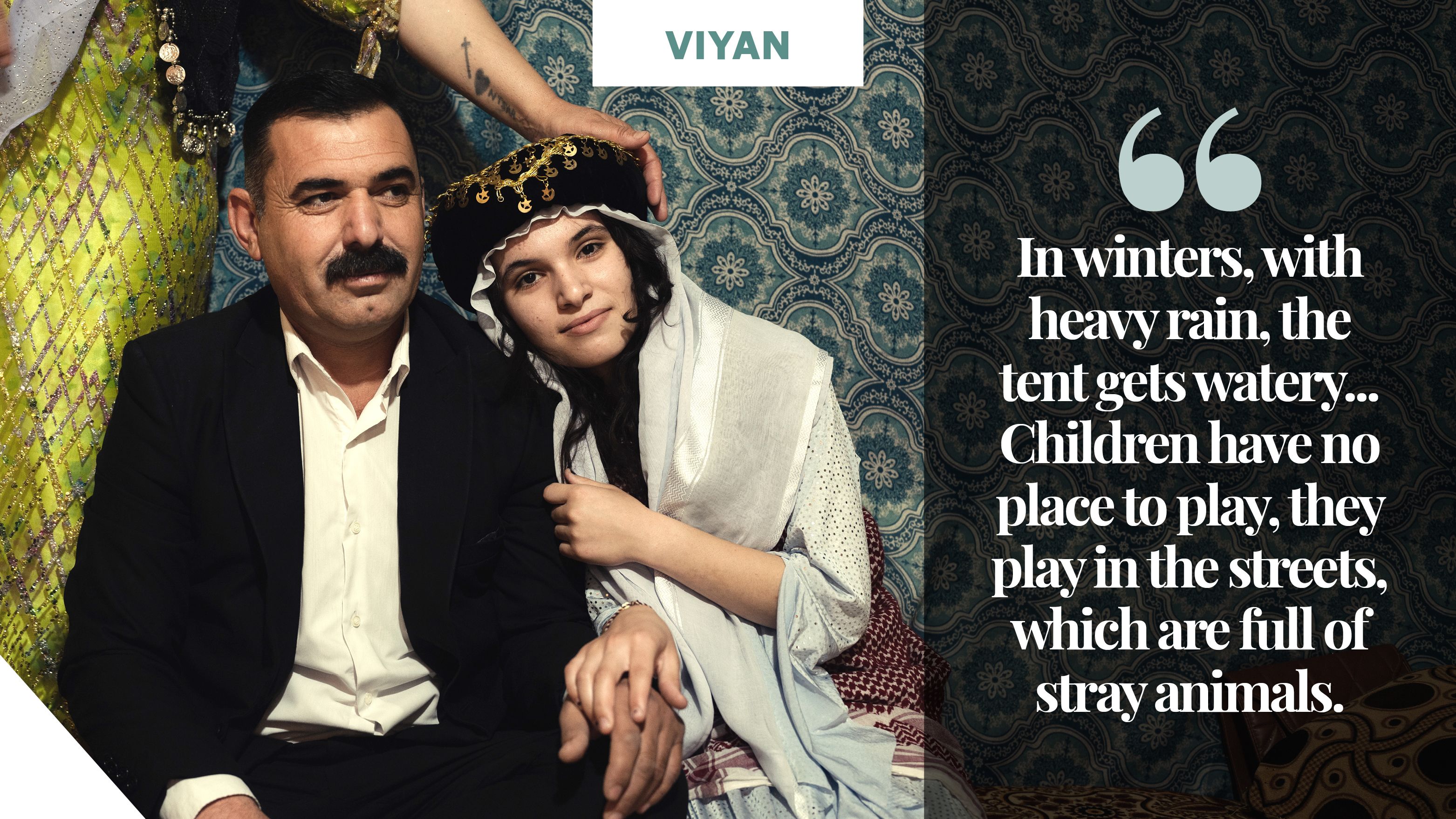

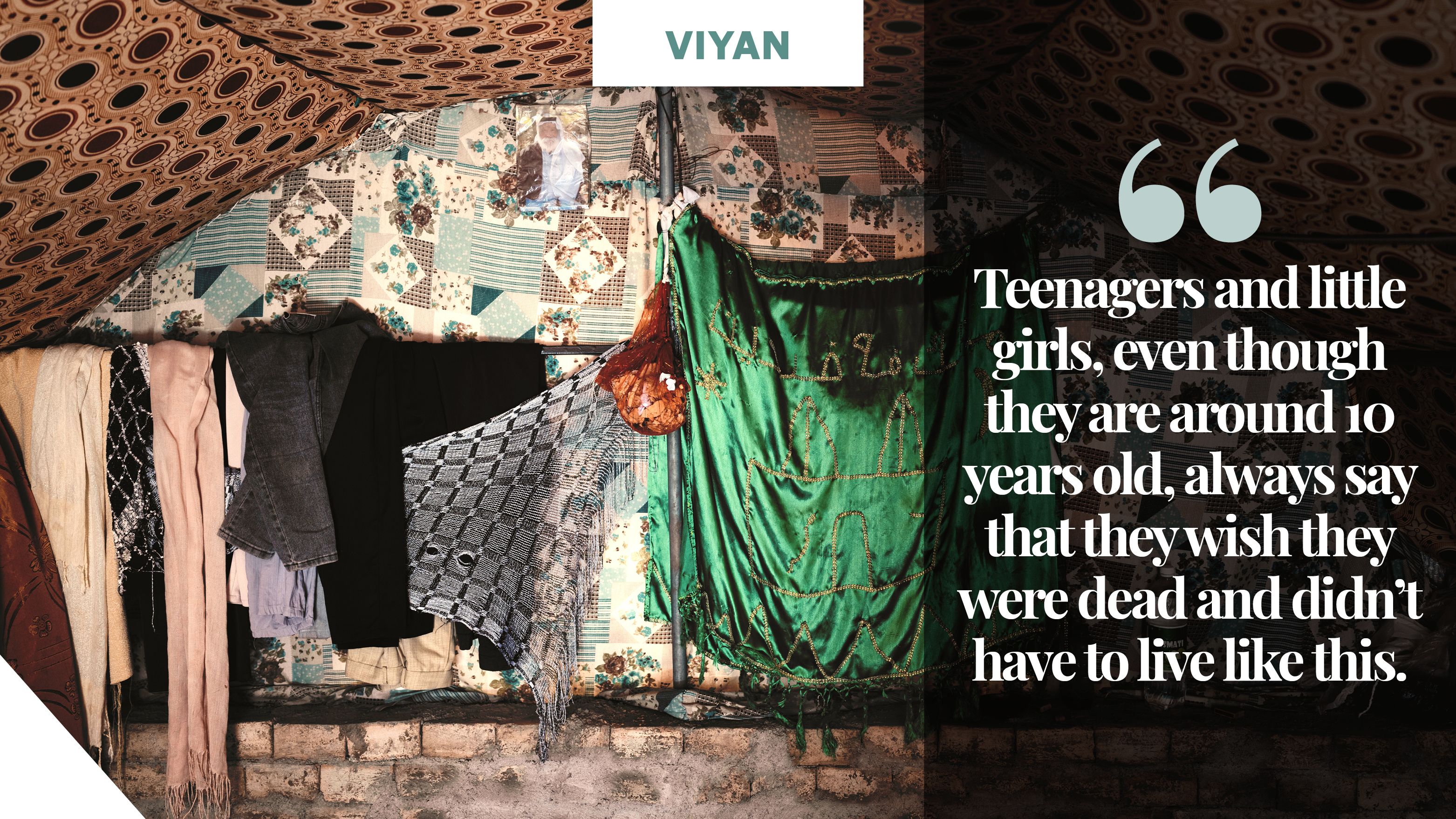

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The family receive child protection services through Save the Children.

The future

The immediate future of the estimated 200,000 Yazidi who remain internally displaced, and of those who have already returned to Sinjar, remains uncertain, at best.

What is certain, however, is that in the years since the genocide, the Yazidi community has shrunk alarmingly. Surveys conducted by Yazda in March 2022 revealed the scale of the demographic disruption to Yazidi society on a village-by-village level. In Ganney, for example, approximately 630 of the 2,775 residents left Iraq, and more than half of the 4,800 people who lived in Sharka have emigrated.

Local statistics such as these echo a troubling bigger picture. In 2005, about 750,000 Yazidis lived in Iraq. By the eve of the genocide in 2014, this had already fallen to about 550,000. Since then, more than 120,000 have fled the country and the region.

“What remains,” as Yazda has pointed out, “is only half of the community’s historic population numbers.”

There is, said Ismael, a stark lesson to be learned from the experience of the Yazidi in Syria.

“There were 80,000-100,000 Yazidis living in Syria in 2011. Today, there are about 4,000, so about 95 percent of the Yazidi community of Syria has already migrated,” he said.

“There is now no functioning Yazidi community in Syria, and the same thing will happen to Iraq.”

If there is to be any hope of halting this exodus, said Shamdeen, “what needs to happen now is what should have happened many years ago, when the region was liberated” from Daesh.

This includes “work on rebuilding what Daesh destroyed in the Yazidi homeland in Sinjar, and restoring the Yazidi temples and schools and clinics” – work that, until now, has been left to NGOs such as Yazda, Nadia’s Initiative and others on the ground.

The Iraqi government, Shamdeen added, “should have had a timeline and a plan to help the community return home, giving them compensation and reparations to be able to restore their homes and to rebuild their farms and livelihoods.”

Matthew Barber delivering aid on Sinjar Mountain in the winter of 2015. The Yazidis are slowly returning home, but "out of a kind of desperation, a lack of options."

Matthew Barber delivering aid on Sinjar Mountain in the winter of 2015. The Yazidis are slowly returning home, but "out of a kind of desperation, a lack of options."

Although the possibly imminent closure of the camps for the internally displaced is an alarming prospect for many who have known nothing else for the past decade, “the sad reality is that in the past 10 years, 95 to 99 percent of the international community’s support has been focused on basically keeping people alive in these camps and feeding them, rather than saying, ‘We need a better, sustainable plan to spend this money to help people return home and have a dignified life, have a normal life, rebuild their homes,’” said Shamdeen.

“We have tried, again and again, with the UN, with the international community. Billions of dollars have been poured into these camps. Everything is temporary. Everything is just to keep people alive until the next day and, to be honest, keeping people in these camps for a decade is tearing apart the very fabric of the community, the culture and the way of life.”

Over the years Yazidi NGOs have published multiple reports on the needs and challenges of the Yazidi community, hosting high-level international and national advocacy and diplomacy gatherings to make sure the voices of communities are integrated into the little decision-making that is happening for Sinjar.

In 2023, Nadia’s Initiative produced a detailed report titled “Rebuilding among the ruins,” which outlined a clear road map for the return of the Yazidi homeland to a semblance of normality, with specific recommendations for the rebuilding of housing and infrastructure, and the restoration of water and sanitation services, healthcare and education, and the creation of jobs.

Most importantly for building the confidence of potential returnees, it called for Yazidi representation in diplomatic initiatives designed to resolve regional disputes, the appointment of a community-nominated candidate as mayor of Sinjar, an end to the historical exclusion of Yazidis from the political processes that govern their lives, and support for the provision of vital documentation, including ID cards, birth certificates, education certificates, land deeds, and paperwork for those who survived Daesh.

“And what I can tell you,” said Shamdeen, “is that it would cost a fraction of what has been spent on the camps, to restore and rebuild the homeland. And to be honest, I’m not sure why they’re not doing that.”

Calls for Yazidi representation in political and public administration roles in Sinjar were also made by Yazda, the Free Yazidi Foundation, and Sinjar Academy in a policy report published in July. “Ten Years After Genocide: The Yazidi Struggle to Recover and Overcome,” is a proposed blueprint for the safe, voluntary and dignified return of Yazidis to Sinjar.

In it, the co-authors wrote that “returns must be practical to be successful, and displaced families should not be forced out of camps or shelters into homelessness,” emphasizing that the camps should be closed only after the voluntary return of families to Sinjar.

The grim situation faced by the Yazidi is summed up by the title of a report published by Yazda at the end of July to mark the 10th anniversary of the genocide: “There is no Future in Sinjar Without Safety and Agency.”

The report was prepared in collaboration with the Middle East Program of the Wilson Center in Washington D.C., and the Zovighian Public Office, which was established to serve communities affected by crises and crimes of atrocity, and has been working hand-in-hand with Yazda since 2015 to create, advocate for and fund survivor-centered, Yazidi-led community initiatives.

After receiving her Nobel Peace Prize in Stockholm in 2018, Yazidi survivor Nadia Murad flew to Baghdad to plead the Yazidis' case with Iraq's President Barham Salih. (Sabah Arar)

After receiving her Nobel Peace Prize in Stockholm in 2018, Yazidi survivor Nadia Murad flew to Baghdad to plead the Yazidis' case with Iraq's President Barham Salih. (Sabah Arar)

The long-term consequences of the genocide and war crimes perpetrated by Daesh in Sinjar have, the report states, “significantly disempowered minority communities, (and) its lasting effects are being felt by every citizen, family, tribe and community.”

It continues: “Rather than zealously transform governance with innovation and equitability, the public administration in Sinjar continues to systemically exclude diversity and minorities, institutionalizing lack of access to security, services and a sustainable future for all Yazidis.”

The dual administration of Sinjar between the Iraqi government and Kurdistan’s regional administration complicates the allocation of essential resources to Sinjar, it adds, perpetuating a political disempowerment at all levels that “extends back to the persecution policies under the administration of the Ottoman Empire and the Arabization campaigns of Saddam Hussein.”

Hopes were raised in October 2020 when the central and Kurdistan governments signed the Sinjar Agreement. This was introduced by the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq as a “new chapter for Sinjar, one in which the interests of the people of Sinjar come first,” and which would “help displaced people to return to their homes, accelerate reconstruction and improve public service delivery.”

Since then, however, the agreement has only gathered dust. Further reinforcing the impression that it is dead in the water, the central government in Baghdad is now pushing for the mandate of its author, the UN Assistance Mission, to conclude by the end of 2025, arguing that “the grounds for the presence of a political mission in Iraq no longer exist.”

Beyond whatever political and geopolitical complexities the future might hold, Haider Elias also fears that many of the children living in the camps will have lost all connection to their culture and heritage by the time their families do manage to return to Sinjar.

“We have children who don’t know what their homes look like, or the temples, the houses of worship,” he said. “They have only seen tents and they don’t know where they are from.

“If you asked a Yazidi child where they are from, they used to say the name of a tribe or a town. But if you ask a child in the camps where they are from, they say, ‘I’m from this camp, or that camp.’ That’s how they identify themselves. The social fabric of the Yazidi and Sinjar has been torn apart.”

If the closure of the camps is mishandled, there are fears it could lead to a community-devastating exodus. There are about 55,000 families still in the camps, between 200,000 and 250,000 people in all, and they fall into three categories.

“A small minority are thinking of nothing else but to emigrate, to Australia, America or Europe,” said Elias. “These people are not going to come back to Sinjar.

“Another, bigger, category will stay in Kurdistan. Some of them have built a small home or have purchased an apartment there. Some have a small business or are employees of the government there.

“But the biggest category of all is those people who cannot emigrate, because they cannot afford to or aren’t eligible, who can’t afford to stay in Kurdistan, where the cost of living is extremely high, and who cannot go back to Sinjar because their homes there have been destroyed. We’re trying, all of us are trying, to find a solution for this category, which is about 50 percent of the internally displaced population.”

Nadia’s Initiative has supplied farming communities with tools, seeds and plants, and since 2018 dozens of farms have been rehabilitated.

Nadia’s Initiative has supplied farming communities with tools, seeds and plants, and since 2018 dozens of farms have been rehabilitated.

As the only English-speaking foreign scholar of Yazidism in the country, and a witness to the genocide, Matthew Barber was invited by Yazidi activists in 2014 to help plead their case at the White House, and in briefings to the governments of Canada, Italy and the UK. In 2015 he became Yazda’s first executive director, and in 2017 he helped edit Nadia Murad’s autobiography.

Today, he sees some Yazidis “are slowly going back to their lives but in a fashion that is much more delayed than it should have been.

“And they’re going back despite the failure to implement the measures that were needed, earlier, in order to facilitate them going back. They’re going back out of a kind of desperation, a lack of options.”

Emigration therefore remains an ambition for many.

“If you asked Yazidi people in the months following the genocide, ‘Do you want to go home to Sinjar or leave the country?’ the dominant response was that they all wanted to leave the country,” Barber said.

“They were traumatized and terrified and they didn’t feel safe, even in the Kurdistan Region. The Peshmerga had abandoned them in Sinjar, so why wouldn’t they abandon them in the Kurdistan Region as well?

“Many people would say, ‘Well, we would like to go back to our home if it would be safe, but we don’t believe it ever will be so we want to leave.’”

This push for emigration, he added, “has been very harmful for the community here. Not everyone is going to leave but it’s the people with higher education levels who do, which means less-educated people end up remaining.”

One step he sees as crucial in efforts to stem the tide of the exodus would be the creation of “a local Yazidi security force, not comprised of Yazidis exclusively but reflecting the demographics of the Sinjar region.” To earn the confidence of the Yazidis “it would have to be under the control of the Yazidi people rather than something external” such as the Peshmerga.

“The second thing that is needed is local governance and administration,” Barber said. “Sinjar is not part of the Kurdistan Region but it was occupied by the Kurdistan Democratic Party after the US invaded in 2003, and from that point forward the KDP, as a political party with militias, dominated and occupied it. This was never something agreed to on paper and was rejected by the central authorities in Iraq, which is why it became one of the disputed territories.”

Dozens of damaged schools have been restored and supplied with new furniture and equipment, and hundreds of voluntary teachers have been trained.

Dozens of damaged schools have been restored and supplied with new furniture and equipment, and hundreds of voluntary teachers have been trained.

The Yazidis “have had two main demands of the international community," he said. "Help in creating a nonpartisan administration for Shingal that is not controlled by any particular political faction, and help in creating a nonpartisan, local security force, under the authority of the requisite ministry in Baghdad, that will help guarantee Yazidi safety and prevent a future recurrence of genocide.

“But we are now a full decade into this crisis and the US has not pursued any meaningful effort to engage with Baghdad and produce either of these two crucial objectives. Sinjar remains without an official administration at present, despite this significant passage of time and widespread international recognition of this case as genocide.”

One obstacle to progress is that Sinjar is “a prized bit of territory” for the Kurdistan Region.

“The Kurds have long had an aspiration to become an independent state and they want to maximize the territory of the Kurdistan Region,” Barber said.

“Another reason is that Sinjar is very strategic territory, being so closely adjacent to the Syrian border. And if they controlled Sinjar, they could control the territory between Sinjar and the Kurdistan Region, which is technically Arab.”

Most importantly of all, he said, “Sinjar is a productive area, agriculturally, full of wheat and barley farmers and a lot of sheep herders as well. And when the KDP unilaterally occupied the area, they controlled the agricultural sector and made sure the produce was sold inside the Kurdistan Region rather than inside Iraq.”

The result of all of this political intrigue is that “there is no stable, normalized system of administration in Sinjar,” Barber said.

“This is unacceptable after a decade. And it’s very unacceptable after the first Nobel Peace Prize winner of Iraq has been on the world stage, meeting world leaders all across North America and Europe, all of whom love to do photo ops with her, and yet no one has pressured the authorities in this country to resolve this problem.”

Life is “OK” for most of the roughly 150,000 Yazidis who have gone back to Sinjar, said Murad Ismael.

“Yazidis are also resilient people; they really work very hard, so a lot of people have managed to reestablish their lives, to some extent,” he added.

Nadia’s Initiative has also supported Yazidi cultural projects, including the restoration of the Sheikh Hassan temple complex in Gabara village in 2021, in partnership with local NGO Sanabel.

Nadia’s Initiative has also supported Yazidi cultural projects, including the restoration of the Sheikh Hassan temple complex in Gabara village in 2021, in partnership with local NGO Sanabel.

But even for these people, the prospect of true “normality” remains wholly elusive.

“I was just speaking to a survivor who is waiting with her family for a visa to go to Australia,” Ismael said. “I asked her, ‘How is life with you?’ and she said, ‘Well, I’m waiting for news about a mass grave they just exhumed. I want to know if my father is there, to know whether he is dead or not.’

“And almost every Yazidi has this thing, that things are ‘fine’ — but actually they are not fine. You can never really recover from genocide, from the loss of a wife or child or husband. Some people learn to live with it but others struggle to do so.”

The plight of the Yazidi has been acknowledged and recognized internationally to a much greater extent than it has within Iraq, or in the Kurdistan Region, said Ismael.

“When you talk to people about the Yazidi genocide they immediately say, ‘What happened to you happened to everybody else.’ They either take a defensive position or they attack you but there is no real, genuine interest in helping the Yazidi community recover socially, spiritually or economically, to become a community that can thrive, that can stay and believe in its homeland.”

As a result, he added: “If you ask Yazidis now if they want to leave Iraq, 90 per cent will say they don’t want to stay in Iraq or in the Kurdistan Region. If the way they treat the Yazidis continues, nobody will stay there and eventually, in 50 years, there will be no Yazidis in Iraq or the Kurdistan Region, except for a few thousand people in villages on top of Mount Sinjar.”

A key issue, said Navrouzov, is that “while the Yazidis are pushing for action, decisions on issues directly related to the community are being made without them. Yazidis need a sense of agency over their own future; they need to see that their voices matter.”

A decade after the genocide that shocked the world, the Yazidis are as vulnerable as ever, due to a combination of international indifference and continuing disempowerment in their homeland

“Where do the Yazidis take it from here?” asks Lynn Zovighian, founder of the Zovighian Public Office, which has been supporting Yazda since its inception and has worked closely with Murad Ismael, Abid Shamdeen, Matthew Barber, Haider Elias and Natia Navrouzov.

“The genocide against the Yazidis is far from over; there is ample evidence that makes clear that they are not safe in Sinjar, in the camps, in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region, and even in countries that are not bringing their foreign Daesh fighters to court.

“So as long as there are clear and measurable conditions for a people to be harmed, in part or in whole, as is stipulated by Article 2c of the Genocide Convention, all eyes must remain focused on protecting and enabling the Yazidi community.

Yazidis light candles at the Temple of Lalish during a ceremony in April 2023 to celebrate the Yazidi New Year and commemorate the coming of light into the world. Their world, however, is still overshadowed by the horrific events of 2014. (Safin Hamid)

Yazidis light candles at the Temple of Lalish during a ceremony in April 2023 to celebrate the Yazidi New Year and commemorate the coming of light into the world. Their world, however, is still overshadowed by the horrific events of 2014. (Safin Hamid)

“Yazidi leaders such as Murad, Abid, Haider, Nadia and Natia must not only push hard to take charge but must also be given all the resources, tools and power to do so, and it is the responsibility of all national and international governments to make sure that happens.”

The Yazidi, Zovighian said, have fought their corner tenaciously.

“No community such as the Yazidis has ever been able to have their genocide recognized in the early days of their suffering,” she added.

“No community has ever represented themselves the way the Yazidis have at the UN Security Council, the European Parliament and around the world. They are a global benchmark, right in the heart of the Middle East, and we should all be supporting and empowering their extraordinary tenacity, wisdom and leadership.

“There can be no room for failed justice and failed return. We must all make sure the Yazidis are welcomed back home safely and wholesomely, and preserved in our region for generations and centuries to come.”

A decade after the start of the genocide, said Navrouzov, “we have passed the moment where we receive a lot of empathy and implement a few projects here and there, with most of the funds not even directly reaching the Yazidi community.

“We need sustainable solutions, we need the truth of what happened, we need justice in the broad sense, and we need to ensure that what happened does not happen again.

“Without this, our ancient community will face extinction, and we will have all failed.”

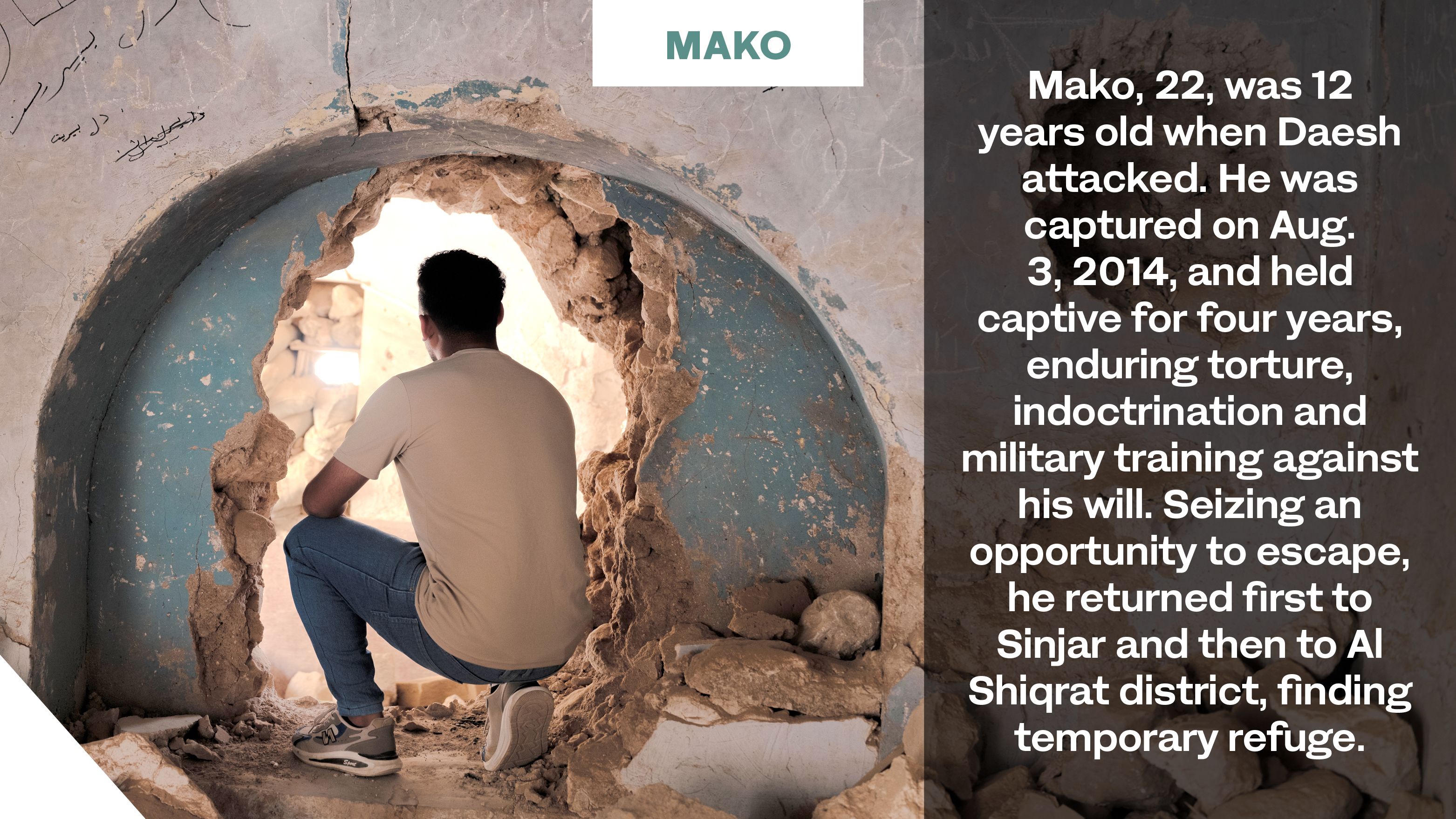

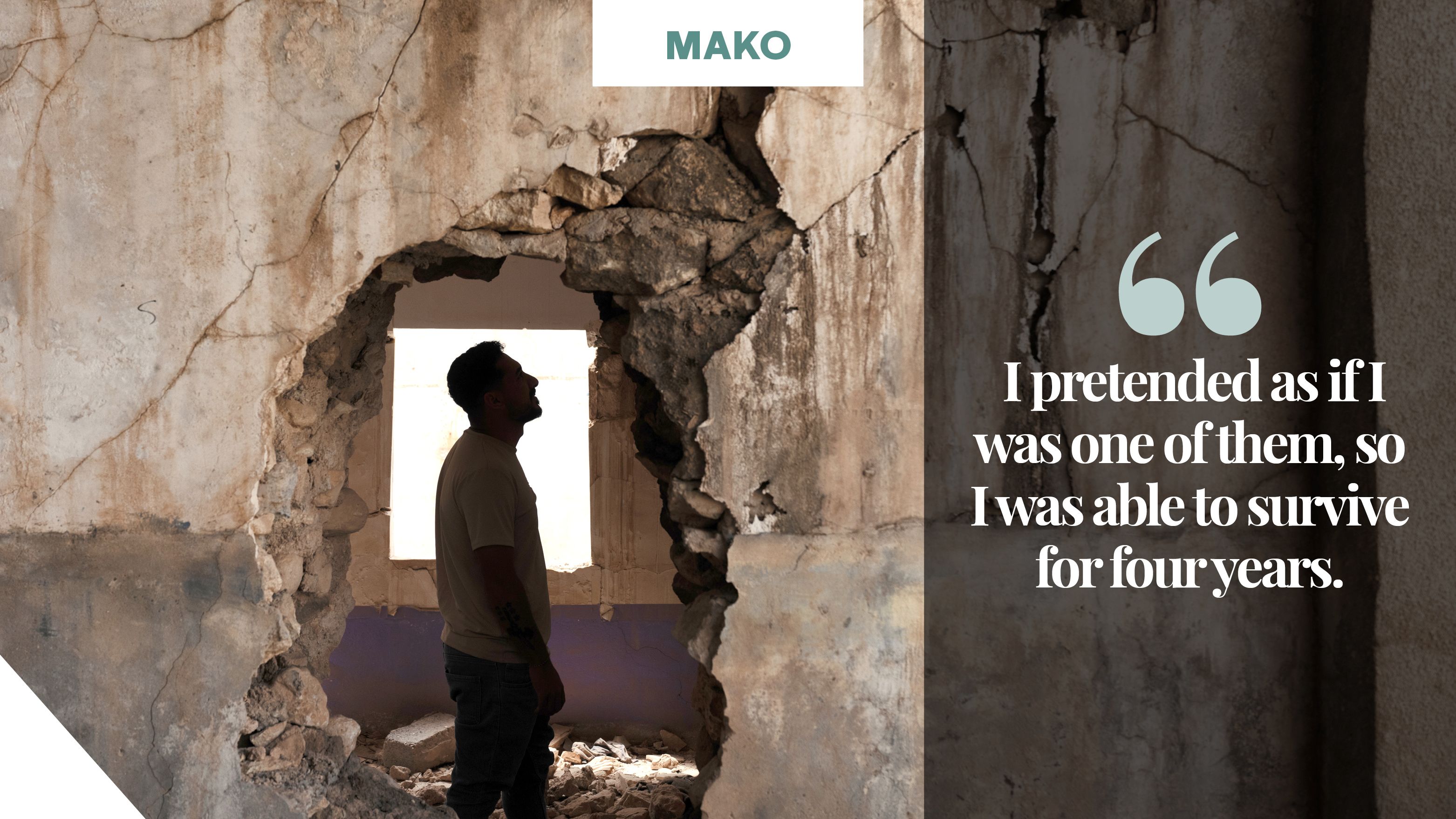

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Mako receives psychosocial support through Save the Children.

Credits

Writing & Research: Jonathan Gornall

Editor: Tarek Ali Ahmad

Creative director: Omar Nashashibi

Designers: Douglas Okasaki, Omar Nashashibi

Graphics: Douglas Okasaki

Head of video production: Hasenin Fadhel

Picture researcher: Sheila Mayo

Copy editor: Liam Cairney

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas

Special thanks: The Zovighian Partnership, Yazda, Nadia's Initiative, Save the Children