A Cup of Gahwa

The taste and traditions of Saudi coffee

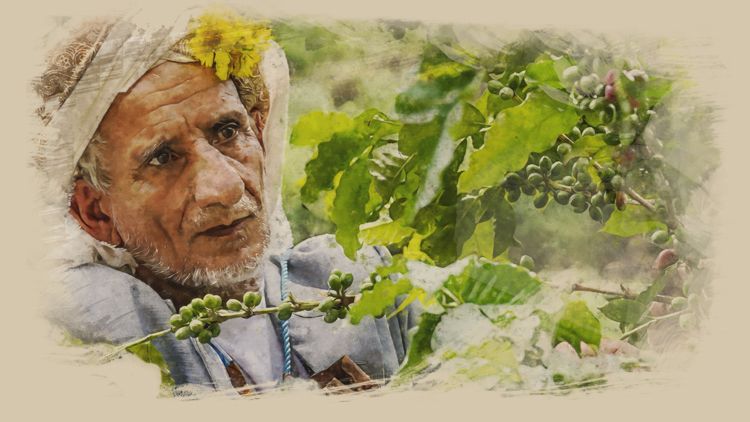

High in the lush green Sarawat Mountains in Saudi Arabia’s far southwest, a man sits barefoot, roasting a handful of coffee beans in a skillet over an open fire.

Uncle Jibran roasting coffee beans on the terraces of Jabal Bani Malik, as his predecessors have done for generations.

He wears a wizrah, the traditional wrap-around skirt favored by the men of the mountains, and is protected from the fierce summer sun by a red-and-white ghotra wrapped around his head.

The coffee trees thrive on terraces cut into the flanks of the Sarawat Mountains.

The coffee trees thrive on terraces cut into the flanks of the Sarawat Mountains.

Against the dramatic backdrop of Jabal Bani Malik, a peak towering over 2,000 meters, he is utterly at one with his breathtaking surroundings as he turns the beans with well-practiced ease.

It is a scene that could have been witnessed in this magical place at any point in the past few centuries.

Abu Mohammed, better known in these parts as Uncle Jibran, is a coffee farmer. He is one of hundreds in the remote and mountainous Saudi province of Jazan who continue to follow a tradition established by their forebears generations ago.

Saudi Arabia might be better known for its deserts, but in this part of the country the prevailing color is green, with hues so vibrant that at times the scenery appears to have been manipulated by an Instagram filter.

The evocative smells of the verdant mountains, mingling with the wood smoke, fill the air with a unique perfume, which, if it could be bottled, would be labelled simply “Jazan.”

And there is no doubt about the top note of this perfume: the scent of Saudi coffee, planted, grown, harvested, roasted, ground and brewed in a style that has been handed down over hundreds of years.

Coffee is not the only crop grown on the mountains. These are largely self-reliant communities. Items that they cannot grow themselves, they buy from a store lower down the mountain. But each family fills its plates and pantries with products from its own land.

Uncle Jibran’s crops include corn, bananas, papayas, chili peppers and even cocoa. His household eats traditionally — meals consist of staples such as rice with farm-raised goat meat, homemade bread and salads.

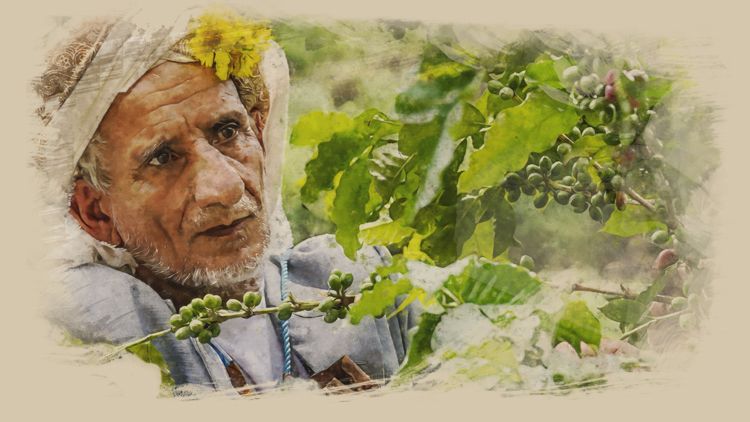

The Khawlani coffee bean: the green gold of Jazan.

But the king of crops on the terraces here, as it has always been, is the “green gold” of Jazan — the Khawlani coffee bean.

A subspecies of Coffea arabica, the first coffee species ever cultivated, Khawlani is named after Khawlan bin Amir, a common ancestor of the mountain tribes who farmed here hundreds of years ago.

Today, coffee is grown on more than 2,500 plantations in three neighboring provinces in Saudi Arabia’s southwest.

With 58,000 plants between them, Baha and Asir together produce about 58 tons of coffee a year.

But it is the most southerly province of Jazan, with 340,000 coffee bushes and an output of 340 tons a year, that is the industry’s regional powerhouse.

Jazan is far from Riyadh, in pace and outlook, as well as distance. Visitors, even from other parts of Saudi Arabia, are few.

At just 11,671 square kilometers, it is the second smallest of Saudi Arabia’s 13 provinces — only Baha, to the north, at under 10,000 square kilometers, is smaller.

In the far south of Jazan province can be found the most southerly point of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This is the village of Muwassam, which sits on the coastal plain of the Red Sea to the west of the Sarawat mountain range and nestles against the border with Yemen to the south.

The provincial capital, Jizan, 60 km north of Muwassam along the coast, is a thousand kilometers from Riyadh. It lies so far south that it is on the same latitude as the Omani city of Salalah, far away on the Arabian Sea.

Uncle Jibran roasting coffee beans on the terraces of Jabal Bani Malik, as his predecessors have done for generations.

Uncle Jibran roasting coffee beans on the terraces of Jabal Bani Malik, as his predecessors have done for generations.

The Khawlani coffee bean: the green gold of Jazan.

The Khawlani coffee bean: the green gold of Jazan.

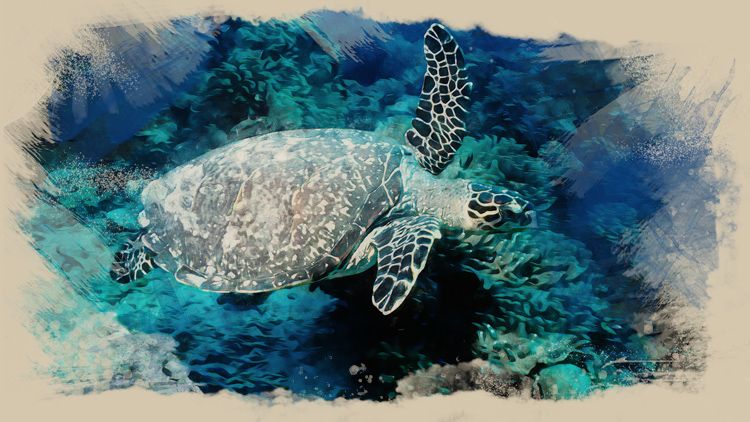

The province of Jazan is as beautiful as it is remote. Framed by the Red Sea to the west, and by the border with Yemen to the east and south, it is a region of extreme natural beauty, from the protected nature reserve of the 100-plus Farasan coral islands off the coast, to the breathtaking Sarawat Mountains in the east.

The province of Jazan extends from the mountains of the interior to the paradise of the Farasan Islands ...

... a group of coral islands designated a marine sanctuary and home to dozens of protected species. (Getty Images)

Farms cling to the slopes of the Sarawat Mountains, blessed with an ideal climate for growing coffee. (Getty Images)

Only up there, in the clean air, fertile soil and lush micro-climate found above 1,800 meters at this latitude, do all the elements necessary for the cultivation of the precious Khawlani beans come together.

Uncle Jibran’s Rayed-Maryam Farm, near the village of Aal Qotail, is situated high in the Sarawat range, clinging to the flanks of Jabal Bani Malik in the Ad-Dayer governorate of Jazan province.

To the east, the border with Yemen is just 7 km away from where Uncle Jibran sits quietly roasting his beans, which explains the many military checkpoints in the region.

Reaching the farm requires a sturdy, four-wheel-drive vehicle and nerves to match. It is only about 100 km to the farm from Jizan Regional Airport on the coastal plain. But a journey that starts out on a smooth four-lane highway takes several hours and becomes increasingly hair-raising, as the winding road narrows and claws its way up into the mountains, one hairpin bend at a time.

While life in the mountains can be tough, it is also beautiful. Seen from the air, the coffee plantations, sinuous ribbons of green carved out along the contours of the mountains, seem to have been poured across the landscape.

Saudi coffee is not widely known around the world. Until now, all coffee grown in Saudi Arabia has been for consumption in the Kingdom, where it is much in demand. But what is rarely appreciated is that, despite the reputations of countries such as Brazil and Colombia as the world’s most famous producers of coffee, it was here, in the Sarawat Mountains, that it all began.

The precise origins of coffee, which today is one of the world’s most popular drinks, are uncertain.

“There is a mythology surrounding that,” said Christopher Feran, a US-based coffee industry consultant who has worked with growers and exporters in countries including Guatemala, Colombia and Ethiopia.

“The real history is that the discovery of coffee would have happened in Ethiopia,” he said. “But the legend is that there was a goat herder named Kaldi who was looking for his goats, which were lost in the mountains somewhere. Eventually he found them eating fruit from a tree, and dancing all over the place. He consumed some of the berries himself, felt invigorated and ran back to the village to share his discovery with everyone.”

Yes, berries — also known as cherries. Strictly speaking, coffee is not made from a bean. The coffee plant is a fruit bush, and the “beans” are the seeds from the fruit that grows on its branches.

The coffee plant grows wild only in Ethiopia, where it was discovered centuries ago, but was first domesticated in Arabia. (Getty Images)

The coffee plant grows wild only in Ethiopia, where it was discovered centuries ago, but was first domesticated in Arabia. (Getty Images)

Myths aside, what is certain is that the Arabica plant, source of the world’s finest coffees, grows wild in only one place — the forests of Ethiopia’s Kafa region.

What is also true is that it was the Arabs who discovered the potential of coffee as a drink and, at some point in the 14th or 15th centuries, first domesticated and began farming the wild plant, transporting seeds or seedlings across the Red Sea for cultivation in the perfect growing environment of the Sarawat range.

The first known written reference to the properties and uses of the coffee plant was by the 10th-century Persian physician Abu Bakr Al-Razi. But, as William Ukers, editor of “The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal” in New York, wrote in his exhaustive 1922 history “All About Coffee”: “The Arabians must be given the credit for discovering and promoting the use of the beverage, and also for promoting the propagation of the plant, even if they found it in Abyssinia (Ethiopia).”

In various histories, and in the UNESCO document proposing Saudi coffee as an intangible cultural heritage asset, credit for introducing coffee to Arabia from Ethiopia is given to one Jamal Al -Din Al-Dhabhani, a 15th-century sheikh of Aden.

It was discovered that the plant grew well on the slopes of the well-watered Sarawat Mountains, and by the late 15th century coffee had become a common crop, and drink, in the region and beyond, claiming a central role in Arab cultural traditions.

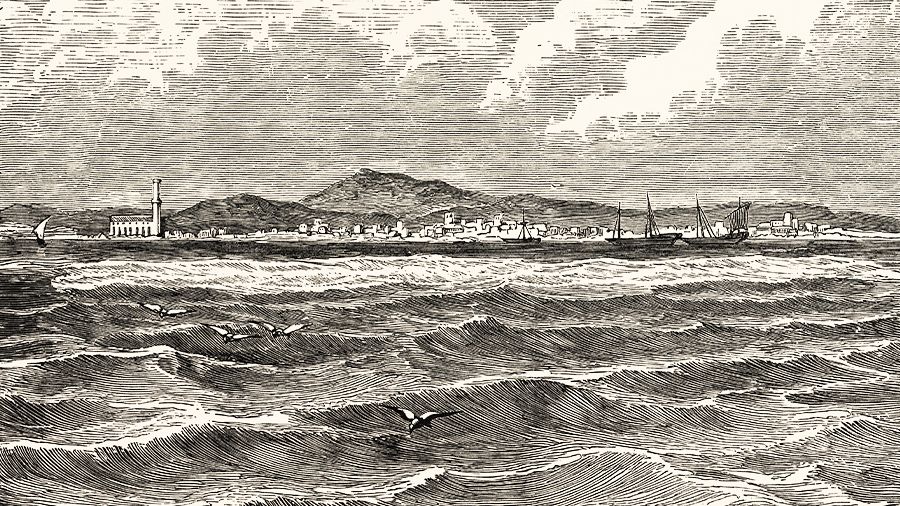

For hundreds of years, the port of Mocha in Yemen was the world's main source of coffee. (Getty Images)

For hundreds of years, the port of Mocha in Yemen was the world's main source of coffee. (Getty Images)

For a while, the Red Sea port of Mocha, a name that would become synonymous with the drink, was the world’s only source of coffee. Exports were carefully controlled — no coffee berries, containing the precious seeds, were allowed to leave Arabia without first having been boiled in water, destroying their ability to germinate. However, wrote Ukers, “with thousands of pilgrims journeying to and from Makkah every year, it was not possible to watch every avenue of transport.”

One tradition holds that the coffee plant first took root outside Arabia in India, in about 1600, after a Muslim pilgrim returned from Makkah with a few seeds.

A ship of the Dutch East India Company, which ended Arabia's monopoly on coffee in the 17th century. (Alamy)

A ship of the Dutch East India Company, which ended Arabia's monopoly on coffee in the 17th century. (Alamy)

What is certain is that as coffee caught on and became an increasingly lucrative product in Europe, in 1616 agents of the Dutch East India Company successfully smuggled a plant out of Mocha.

It was the beginning of the end for Arabia’s relatively brief domination of the coffee market. Mocha’s importance declined as Arabica plantations sprang up around the world, first in the Dutch colonies of Ceylon, Java and Sumatra, and later in the Caribbean and Latin America.

The heritage of Saudi coffee is inextricably bound up with the history of Saudi Arabia — Jazan and Asir, along with the neighboring province of Najran, have been formal parts of Saudi Arabia since the Kingdom’s foundation in 1932.

Historically, almost all the coffee produced in Saudi Arabia has been for domestic consumption, with Saudis among the biggest consumers of coffee per capita in the world.

Now, however, in the Year of Saudi Coffee, the Kingdom’s government is actively encouraging farmers to scale up what for generations has been essentially a cottage industry. It is also promoting Saudi-grown coffee as a symbol of national heritage and a potentially valuable export product, with the aim of raising farmers’ living standards and encouraging young people to follow in the footsteps of their forebears.

Ahmed al-Malki and his son Mansour, 11, harvest Khawlani coffee beans on their farm in Saudi Arabia's mountainous Jazan province. (AFP)

Coffee farming in Saudi Arabia has changed little in hundreds of years. By necessity, production of what is recognized as one of the finest coffees in the world remains a lengthy, time-consuming and labor-intensive business, involving the men, women and children of every family that farms the mountain terraces.

Farah al-Malki, 90, and his grandson Mansour harvesting Khawlani coffee beans, as their family has for generations. (AFP)

As Saudi Arabia’s UNESCO submission puts it: “Families encourage youngsters to work in the lands, starting with minor tasks, until they develop their skills and know-how needed to cultivate coffee trees and process the coffee beans. Boys accompany their fathers in the planting, harvesting, dehydrating and pruning and repairing terraces, while girls help their mothers in the picking, peeling and grinding process.”

Once picked, the ripe fruits of the coffee trees are laid out to dry in the heat of the sun. (AFP)

All this “ensures the transmission of the practice through generations,” so that “young people will have enough knowledge and skills to operate their own farms in the future.”

Of all the skills required, patience is perhaps the key virtue of the successful coffee farmer. Growing coffee is not a process that can be hurried.

The province of Jazan extends from the mountains of the interior to the paradise of the Farasan Islands ...

The province of Jazan extends from the mountains of the interior to the paradise of the Farasan Islands ...

... a group of coral islands designated a marine sanctuary and home to dozens of protected species. (Getty Images)

... a group of coral islands designated a marine sanctuary and home to dozens of protected species. (Getty Images)

Farms cling to the slopes of the Sarawat Mountains, blessed with an ideal climate for growing coffee. (Getty Images)

Farms cling to the slopes of the Sarawat Mountains, blessed with an ideal climate for growing coffee. (Getty Images)

Ahmed al-Malki and his son Mansour, 11, harvest Khawlani coffee beans on their farm in Saudi Arabia's mountainous Jazan province. (AFP)

Ahmed al-Malki and his son Mansour, 11, harvest Khawlani coffee beans on their farm in Saudi Arabia's mountainous Jazan province. (AFP)

Farah al-Malki, 90, and his grandson Mansour harvesting Khawlani coffee beans, as their family has for generations. (AFP)

Farah al-Malki, 90, and his grandson Mansour harvesting Khawlani coffee beans, as their family has for generations. (AFP)

Once picked, the ripe fruits of the coffee trees are laid out to dry in the heat of the sun. (AFP)

Once picked, the ripe fruits of the coffee trees are laid out to dry in the heat of the sun. (AFP)

So far, so traditional for a process that can trace its roots back hundreds of years. But now coffee farming in the Sarawat Mountains is finding itself fast-forwarded to the 21st century, bolstered by investment and modern marketing techniques designed to raise the global profile of the Khawlani coffee bean and put it where it belongs — among the ranks of the world’s finest specialty coffees.

Judged by the standards of the Specialty Coffee Association, any coffee that scores 80 points or more on a 100-point scale can be described and marketed as a specialty coffee.

“We are proud to say,” says Ali Sheneamer, CEO and co-founder of the Jabaliyah coffee company, which is working with the farmers of Jazan, “that we have actually produced, out of this region, specialty coffees scoring 84, 85 and 86.”

Ali Sheneamer, CEO and co-founder of coffee company Jabaliyah, talking about the company.

In May 2022, the Kingdom’s Public Investment Fund launched the Saudi Coffee Company, unveiling plans to invest SR1.2 billion ($319 million) over 10 years to develop the national industry and boost production from under 400 tons to 2,500 tons a year.

In order to build expertise across the industry and encourage more young people into coffee farming, the company plans to establish an academy, “where Saudi Arabian professionals, entrepreneurs, coffee plantation owners and farmers can receive the training and knowledge they need to help them start their own businesses.”

The domestic coffee market alone is huge and growing fast. According to a report by global business analysts Euromonitor International in January 2022, coffee consumption in Saudi Arabia grew by 4 percent a year between 2016 and 2021, and is forecast to increase by a further 5 percent a year up to 2026, reaching an expected annual consumption of 28,700 tons.

But as well as ensuring Saudi coffee takes a larger share of the domestic market, the Saudi Coffee Company also aims to “position the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as a global leader in the coffee production industry.”

Jeddah-based company Jabaliyah is one of its private-sector partners in this mission, working with Uncle Jibran and other farmers in Jazan province. Sheneamer, the company’s CEO, lives in Jeddah with his family, but is a native of Jazan and visits the farms as often as possible.

The coffee business, he believes, is all about family.

“Saudi coffee is a heritage, it’s a culture. It is part of us. It is what we gather around as family, and for the farmers it’s a family member. Coffee is part of their roots. This has been here for hundreds of years, part of the generations — their fathers, grandfathers, great grandfathers,” he said.

“And it is part of the image of Saudi and the brand of Saudi. It is a sign of generosity, which is who we are in Saudi Arabia.”

On the terraces in the shadow of Jabal Bani Malik, Uncle Jibran invites Sheneamer to sit with him. The Jabaliyah boss wears a traditional headpiece, made from local flowers by boys and worn only by men in the region. The flowers are said to have medicinal properties and to ward off headaches, but they also serve as a halo of portable perfume.

While by tradition the younger person offers coffee to the older, it is unclear which of the two men is the senior, so Sheneamer graciously pours a cup for Uncle Jibran.

Coffee is a tradition firmly anchored in Saudi culture, inextricably linked to rituals of hospitality.

Together, the two men contemplate life, while Uncle Jibran sits quietly stirring his beans, to the sound of circling birds chirping above and the bleating of goats on a terrace below.

The farmer has kept an eye on the sky and the darkening clouds gathering over the mountain. His head tilts to one side as the birds suddenly fly away, and he announces it is time to go indoors. It is about to rain.

Farmer Uncle Jibran talking about the coffee farming process.

The pitter-patter of heavy drops falling on the leaves of the coffee plants is music to the ears of every farmer on the mountainside. Jazan might be far from the fast-paced modern world, but the farms are beginning to experience the same effects of climate change as the rest of the planet, and the region has been plagued by unseasonal drought.

Deprived of the seasonal rains that previously have fallen reliably for centuries, coffee farmers have had to resort to shipping in water. Given the treacherous roads, it is a difficult, hazardous job bringing up the tanks and the networks of dark pipes, which stretch out over the landscape like so many spiders’ legs.

It is also expensive, and the cost is only partially offset by government subsidies.

The farmers in the area know each other, but operate independently. Many live in multigenerational homes, with grandparents, parents and children all under one roof. Uncle Jibran, who is also the local imam, leads the prayers five times a day. He collects the men of the town to perform their religious duty, and they take advantage of the gatherings to check on each other.

This remote community looks after its own. But in the face of forces beyond their control there is only so much they can do, and the promise of further support from the Saudi Coffee Company is more than welcome, and seen as a lifeline for a tradition.

Farming is in Uncle Jibran’s blood, passed down from generations that stretch “too far back to know for sure.” He has fond memories of going to the farm with his father and grandfather as a child. But as a young man, hoping for job security and a better income, he decided to try another profession and became a teacher.

For more than 20 years he taught Arabic at the local boys’ school, but found he missed the rhythm of farming life. When the opportunity presented itself, he took early retirement and exchanged chalkboards for the rich soil of the mountain.

He has traded-in the bigger income, but says the reward of being so close to what he loves has been priceless. And he has not left teaching behind completely — schoolchildren often come to his farm on field trips.

Some, no doubt, will follow in Uncle Jibran’s footsteps, perhaps inspired by the determination of the Saudi Coffee Company to promote and develop farming in Jazan, part of a broader strategy to position the Kingdom “as the home of one of the most popular coffee beans in the world.”

Certainly, Sheneamer believes that the company, backed by the marketing and financial know-how of the Public Investment Fund, will “make a big difference,” turning Saudi coffee into one of the soft forces that deliver a positive global image about the quality of the Kingdom’s products, heritage and culture — as well as returning coffee to its origins.

“When people talk about coffee today, they talk about Brazil, Colombia and other places,” he said. “Our ambition is that one day, they will go back to the origin when they talk about coffee, where the first thing that comes to people’s minds is Saudi Arabia.

“Because this is the origin of Arabica.”

Credits

Writers: Jonathan Gornall, Jasmine Bager

Editors: Tarek Ali Ahmad, Noor Nugali

Creative directors: Omar Nashashibi, Simon Khalil

Designers: Omar Nashashibi, Douglas Okasaki

Research: Leen Fouad

Graphics: Douglas Okasaki, Farwa Rizwan

Video producer: Hassenin Fadhel

Video editor: Abdulrahman Shalhub

Videographers: Mohammed Albijan , Abdullah Aljabar

Photo research: Sheila Mayo

Translation: Charbel Merhi, Caline Fares, Joelle Sleiman, Joy Geryes and Rima Barakat

Copy editor: Les Webb

Social media: Jad Bitar

In collaboration with: Jabaliyah, KSA Ministry of Culture

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas